Growing up in Chicago’s Edgewater neighborhood in the 1970s, Mario Rueda remembers being surrounded by Cuban people and culture.

“Our neighbors were Cuban,” he said. “All our family friends were Cuban. The first person I met in grade school, who translated for me, was Cuban.”

As a kid, Rueda regularly walked past St. Ita Church, with its large Cuban congregation, and visited La Plaza, a grocery store owned by a Cuban family. The owner of the store even wrote recommendation letters for Rueda’s family members when they immigrated from Mexico.

But when he goes back to Edgewater today, Rueda said the Cuban community he grew up with seems to have vanished.

So he asked Curious City what brought Cubans to Chicago during the 20th century — and what happened to the Cuban enclaves they created.

Drawn to Chicago by factory jobs, family connections and a government relocation program for Cuban exiles, Cuban Americans were the third-largest Latino group in Chicago in 1970. Anchored by Catholic churches and Cuban grocery stores, clusters of Cuban families formed in neighborhoods like Edgewater, Irving Park and Logan Square. And though they’re less conspicuous today than in places like Miami or New York City, Cuban Americans continue to make their presence felt in Chicago.

“La tierra de frío y trabajo”

Cubans started coming to Chicago as early as 1898.

That year, the first all-Black regiment of the National Guard went to Cuba following the Spanish-American War. In a letter from December 1898, a member of the Eighth Illinois Regiment wrote, “There is much marrying among American soldiers and Cuban women. Three of the boys of our company have taken unto themselves Cuban wives already.” Some of these soldiers returned with their new wives to Chicago, as writer Achy Obejas reported for the Chicago Tribune. These women became some of the earliest known Cubans to make their home in the city.

But the Cuban population in Chicago remained small through the mid-20th century.

That changed after the Cuban Revolution, which saw Fidel Castro’s rise to power in 1959. Several hundred thousand Cubans came to the U.S. from Cuba in the first decade after the revolution ended. My dad and his family were among them, which is what drew me to Rueda’s question about Chicago Cubans.

Carlos Eire, professor of religious studies at Yale University, was part of Operación Pedro Pan, or Operation Peter Pan, a program that brought thousands of unaccompanied Cuban children to the United States between 1960 and 1962. Once in the U.S., Eire and his brother were placed with foster families, like other Pedro Pan kids.

But when the Cuban Missile Crisis occurred, travel to the U.S. from Cuba abruptly ended. Many parents who’d sent their children over with Operación Pedro Pan, under the expectation they’d soon be reunited, had to wait several years to join them.

“My foster family — nice as they were, wonderful as they were — couldn't keep us,” said Eire, who chronicles his journey in Waiting for Snow in Havana, a book my dad had on his bookshelf when I was in middle school. “So they put us ‘temporarily’ in a foster home for juvenile delinquents,” he continued. “And they forgot about us.”

As more and more Cuban exiles settled in Miami in the 1960s, there was backlash — especially from the city’s white, non-Latino residents.

“Anglos in Miami, as Cubans started coming in, they got scared,” said María de los Ángeles Torres, distinguished university professor of Latin American and Latino Studies at the University of Illinois Chicago and the author of several books about Cuban exiles. “And they got even more scared when they figured out that we were not going back to Cuba.”

Torres said it became common to see pancartas, or placards, outside apartment buildings for rent in Miami that read, “No children, no pets, no Cubans.”

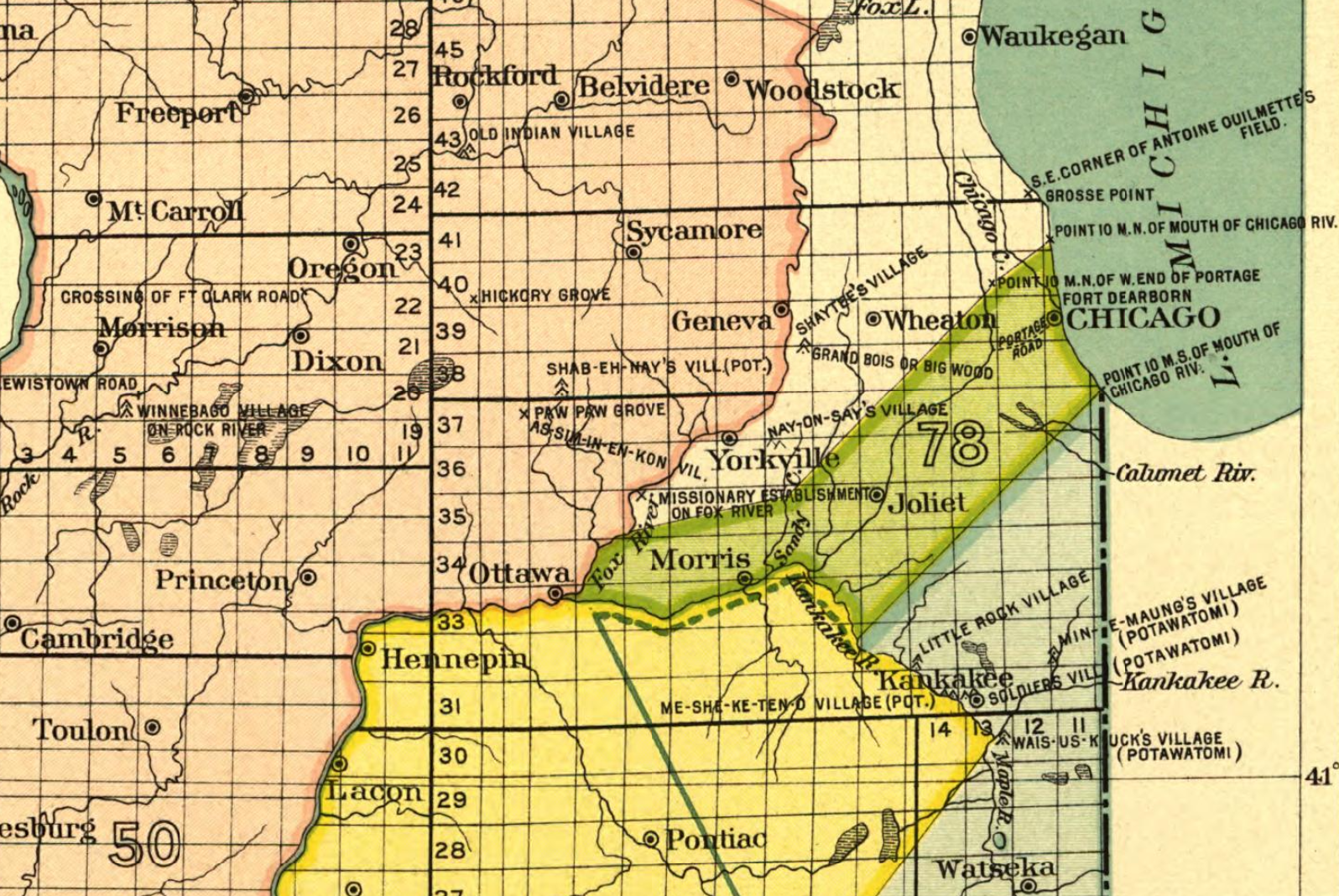

Facing mounting public pressure, the federal government led a series of relocation programs to get Cubans out of Miami and into other cities. “Chicago was one of the major areas of relocation,” Torres said.

As Torres documents in her book In the Land of Mirrors, about 20,000 Cubans were resettled in Illinois during the 1960s as part of these initiatives.

Cubans were sent to “la tierra de frío y trabajo” — the land of cold and work, in Eire’s words — for lots of reasons, but one of the biggest was jobs.

Eire’s uncle, an architect from Havana, was sent to Bloomington, Illinois through a program that relocated Cuban professionals. And he remembers his mother’s experience with a case worker who asked, “‘You don't speak English? … And you don't have any professional skills? We'll send you to Chicago. They’ve got so many factories there, they’ll hire you.’”

By 1970, there were about 15,000 Cubans living in Chicago, according to a report published by the Chicago Department of Planning and Development. Though their numbers were still relatively small, Cubans had grown to be the third-largest Latino group in Chicago, behind Mexicans and Puerto Ricans.

The Malecón of the Midwest

Once they arrived in Chicago, Cubans settled in lots of different neighborhoods. One of the most popular neighborhoods for Cubans was Edgewater on the far North Side. While it was a far cry from Cuba, Eire said there were certain ways in which the lakefront enclave felt familiar — or familiar enough.

“My mom kept saying, ‘Oh, this is just like Havana. You’ll feel at home here,’" he said. "Especially because we were only two blocks from the lake.”

Eire remembers the old Edgewater Beach Hotel, from a certain angle, even looked a bit like the Hotel Nacional in Havana.

Grocery stores owned by Cuban families like La Única and churches with large Cuban congregations like St. Ita became hubs of Cuban social life, which helped draw more Cubans to the area.

Plus, there was just good old-fashioned neighborhood magnetism: When one family moves in, their cousins or friends might decide to move there, too.

At Nicholas Senn High School, Eire remembers his principal had a giant world map on a wall, with pins marking cities and countries across the globe that students’ families had come from.

“You couldn’t even see [Cuba] on the map because of all the pins,” he said.

Political divisions

In the late 1960s and especially into the ’70s, political divisions among Cuban Americans became more pronounced and solidified, as María de los Ángeles Torres documents in In the Land of Mirrors. Against the backdrop of radical politics and upheaval present more broadly in the U.S. at the time, the Cuban American community was very politically polarized.

And that was especially true in places like New York City and Chicago.

In 1968, Cuban Power, a far-right organization, bombed a Mexican tourist office in downtown Chicago because Mexico had maintained diplomatic relations with Cuba.

And Chicago was home to a number of members of Abdala, a Cuban exile student group that used political writings and direct action to further their aim of replacing Fidel Castro.

On the other side, there was the Antonio Maceo Brigade, a political organization composed of Cuban Americans who wanted to build relationships with the Cuban government.

Torres, who was part of the group, said many of its members had been active in the Chicano movement, the Puerto Rican independence movement and other social and political movements in Chicago before deciding to turn their focus on Cuba.

“We all found ourselves really kind of being odd people, bichos raros, within these movements, because we weren't part of any of these communities but we were in solidarity with them,” she said.

The Antonio Maceo Brigade was an international organization, Torres explained, but they had a chapter in Chicago. And they ended up playing a large role in the changing travel policy between the U.S. and Cuba, which had made family visits impossible for years.

Some of the group’s members — whose attitudes towards the Cuban government eventually shifted — went on to become important figures in Chicago politics.

Torres, for example, became the first executive director of Mayor Harold Washington’s Advisory Council on Latino Affairs in the 1980s. Another Cuban American, Natalia Delgado, was nominated by Washington to become the first Latino member of the Chicago Transit Authority Board.

“So these super progressive Cubans became part of the government and became very influential,” said Achy Obejas, who worked as a journalist for the Chicago Tribune for more than two decades. “Even in Miami, the Cuban Left never achieved something like that. That happened in Chicago in a very unusual way because of the Washington campaign.”

Tania’s

The fact that Chicago’s Cuban community was so polarized made it all the more significant that there were neighborhoods — and particular places within them — where Cuban Americans from across the political spectrum intermingled.

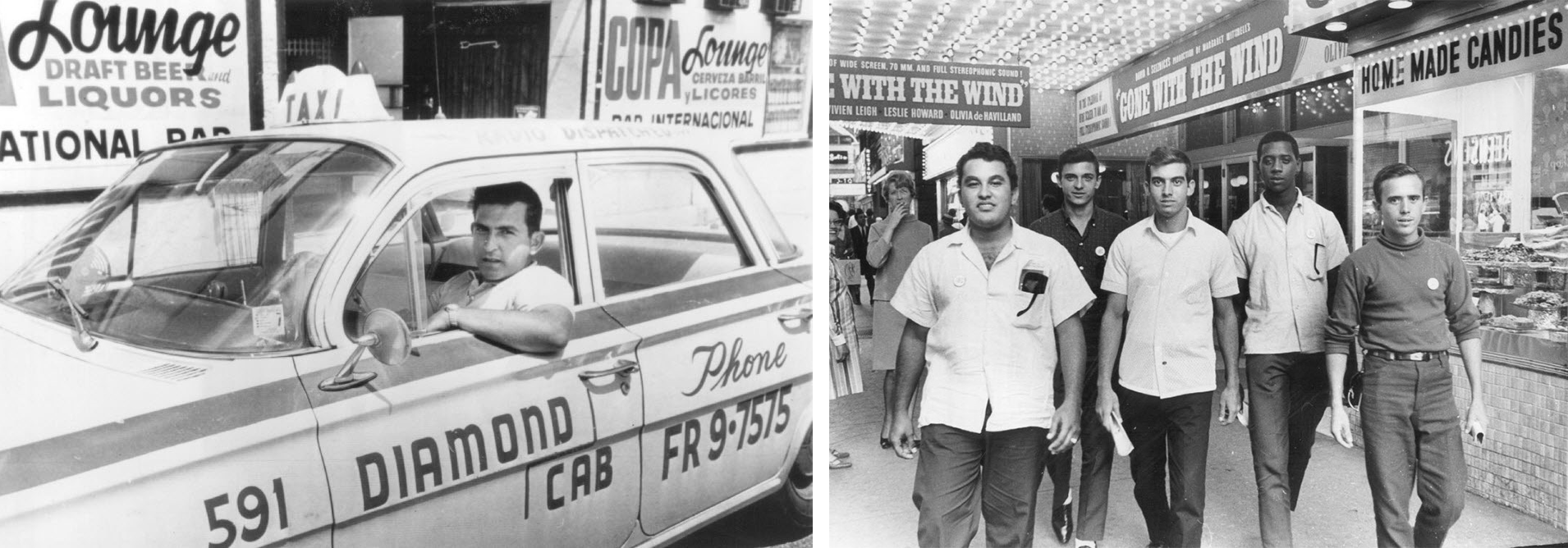

Besides Edgewater, the other Chicago neighborhood that became a Cuban stronghold during the 1970s was Logan Square. And of all the Cuban businesses in the area, perhaps the best known was Tania’s: a bodega, restaurant and nightclub on Milwaukee Ave., across from the Logan Theatre.

“This place was kind of a demilitarized zone,” Obejas explained. “It was one of these places where everybody could go, regardless of their political opinions.”

Owner Elias Sanchez initially worked at a factory making staplers and other office supplies after he came to Chicago from Camagüey, Cuba.

But he had a knack for business, so he opened Tania’s with his wife, Martha, in 1976.

“The grocery, la bodega, it was a butcher shop — you could smell the blood,” said Obejas. “But once you opened the door to the back, it was a completely different universe.”

The menu was filled with Martha’s family recipes. Her black bean soup was apparently Mayor Harold Washington’s favorite; according to Martha, the mayor always ordered extra to take with him after his meal.

And Tania’s became known for its live music. “Elias would dig up these guys who had played in La Orquesta Siboney in 1943,” Obejas said. “They were all, like, on their last breath. But they would come in, they would play the weekend, and the music was incredible.”

“It was like getting into a [department store] elevator on Christmas Eve,” said Aldo Pedroso, Jr., who visited Tania’s with his family. “I’ve never been anywhere — not any club — that packed.”

And it wasn’t just Cuban Americans who flocked to Tania’s. The restaurant was extremely popular amongst the city’s Puerto Ricans, Mexicans, Ecuadorians — and of course non-Latino Americans.

Celebrities like Celia Cruz, Gloria Estefan and Paquito D’Rivera stopped in to eat and listen to live music at Tania’s when they were in Chicago.

One of the most beloved figures at Tania’s was Orestes, the maître d' and waiter. Crowds would form around him and whoever he was dancing with — often Martha — to admire his salsa and merengue moves.

One of the most beloved figures at Tania’s was Orestes, the maître d' and waiter. Crowds would form around him and whoever he was dancing with — often Martha — to admire his salsa and merengue moves.

“People love it, [to] see the Cuban music, and Orestes dancing,” said Sanchez. “[He] is like an icon over there at Tania's.”

After a fire in the 1980s, Sanchez rebuilt Tania’s to make the space larger and more upscale.

“He had a policy of absolute open doors,” Obejas said of Sanchez. “So it drew a lot of the younger, progressive Cubans, and a lot of Cuban queers. … And so this became a very interesting place.”

Tania’s was in some ways a microcosm of Chicago’s Cuban American community during the 1970s and ’80s. The Cuban population here was sizable but a lot smaller than in Miami, meaning people who might not seem to have much in common beyond their shared cubanidad ended up intermingling. And at the center of it all was Tania’s, which because of its “open-door policy” Obejas described became a place where lots of different people felt at home.

Tania’s remained the epicenter of Cuban nightlife in Chicago up until it closed. The venue’s final night was a New Year’s Eve bash on December 31, 1998, which was attended by more than 500 people, according to Sanchez.

“Adiós, Chicago querido”

By the 1980s and ’90s, Chicago had lost a lot of its manufacturing jobs. And when the jobs disappeared, so did some of the people who had come to the city for them decades earlier.

“I remember that somebody came up with this poem, kind of a refrain,” said Carlos Eire. “Adiós, Chicago querido. Tierra de frío y trabajo. Aquí dejo mi abrigo, y me voy para carajo. Goodbye, Chicago, land of cold and work. I leave you my coat. And I go to hell.”

“I remember that somebody came up with this poem, kind of a refrain,” said Carlos Eire. “Adiós, Chicago querido. Tierra de frío y trabajo. Aquí dejo mi abrigo, y me voy para carajo. Goodbye, Chicago, land of cold and work. I leave you my coat. And I go to hell.”

A number of people interviewed for this story said they remember watching more and more of their Cuban friends and family members leave Chicago during these decades. Many of those who left went to Miami, where the Cuban culture — and warmer weather — has huge appeal for Cuban Americans.

However, the Cuban Americans that remained continued to make an impact on Chicago cultural institutions, religious organizations, schools and universities and more.

There’s perhaps no one who embodies this more than Angelina Pedroso, a Cuban American educator who taught at Northeastern Illinois University (NEIU) for more than 40 years.

Pedroso was the daughter of Juan Gualberto Gómez, one of the leaders in the Cuban War of Independence against Spain in the late 1800s. Gómez was a journalist and activist who fought not just for Cuban independence but also for racial equality. And he was a close friend of Jose Martí, the Cuban national hero after whom a section of Chicago’s Milwaukee Ave. gets its honorary street name.

Influenced by her father, Pedroso went to law school in Cuba. But when she arrived in Chicago in the late 1950s, she was no longer able to practice law. As she applied to jobs in the city, she faced discrimination on multiple fronts: as someone who was an immigrant, a woman and Black. Her son, Aldo Pedroso, Jr., remembers his mother returning from an early job interview. The hiring manager, who’d been cordial on the phone, took one look at Pedroso and knocked the documents she’d brought with her to the ground, saying, “Now pick them up and get out.”

When she got a job teaching Spanish at NEIU, Pedroso threw herself at it with gusto. According to Aldo, his mother was often the only person at department meetings who had read school handbooks and policy documents line for line, and knew them practically by heart. She used that to advocate on behalf of her students.

“She’d get to work at seven o’clock every morning, and there would be a line of students waiting to speak to her,” Aldo said, “and she’d speak to every one.” Today, NEIU’s Center for Inclusivity and Cultural Affairs is named after the late Pedroso.

Aldo, who still lives in Chicago, said despite not having a particularly visible Cuban community in the city today, he still feels strong ties to his Cuban identity.

“I feel Cuban more than American,” he said.

While many Cubans did move to Miami, the numbers that are available suggest the Cuban population in the Chicago area actually hasn’t changed all that much since the 1970s. As of 2021, there were around 18,000 Cubans living in the Chicago metro area, according to demographers at the Pew Research Center.

As some people moved out, others moved in.

What has changed is how concentrated Cubans are in particular Chicago neighborhoods, like Edgewater or Logan Square.

Some families moved to the suburbs: the Pedrosos, for example, moved from Hyde Park to Skokie. Others were dispersed into neighborhoods across the city. And the places they created — like Tania’s — went with them.

“There were physical places,” said Obejas. “They just were ephemeral. They didn’t last very long.”

Maggie Sivit is Curious City’s digital and engagement producer. She can be reached at msivit@wbez.org

Before the law passed, municipal departments were responsible for responding to calls about feral cats in the area.

Before the law passed, municipal departments were responsible for responding to calls about feral cats in the area.

Because their zip code is considered a

Because their zip code is considered a

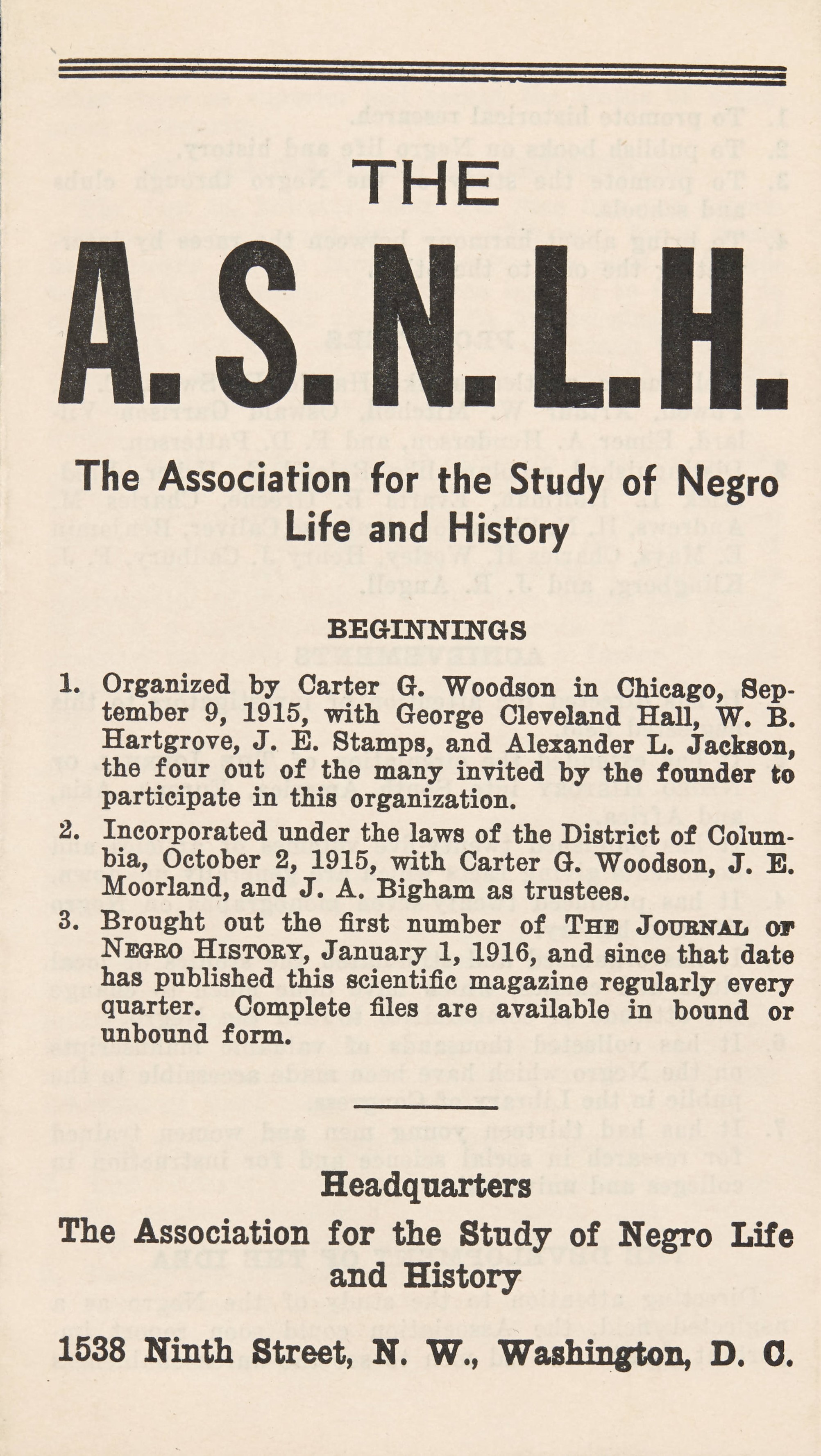

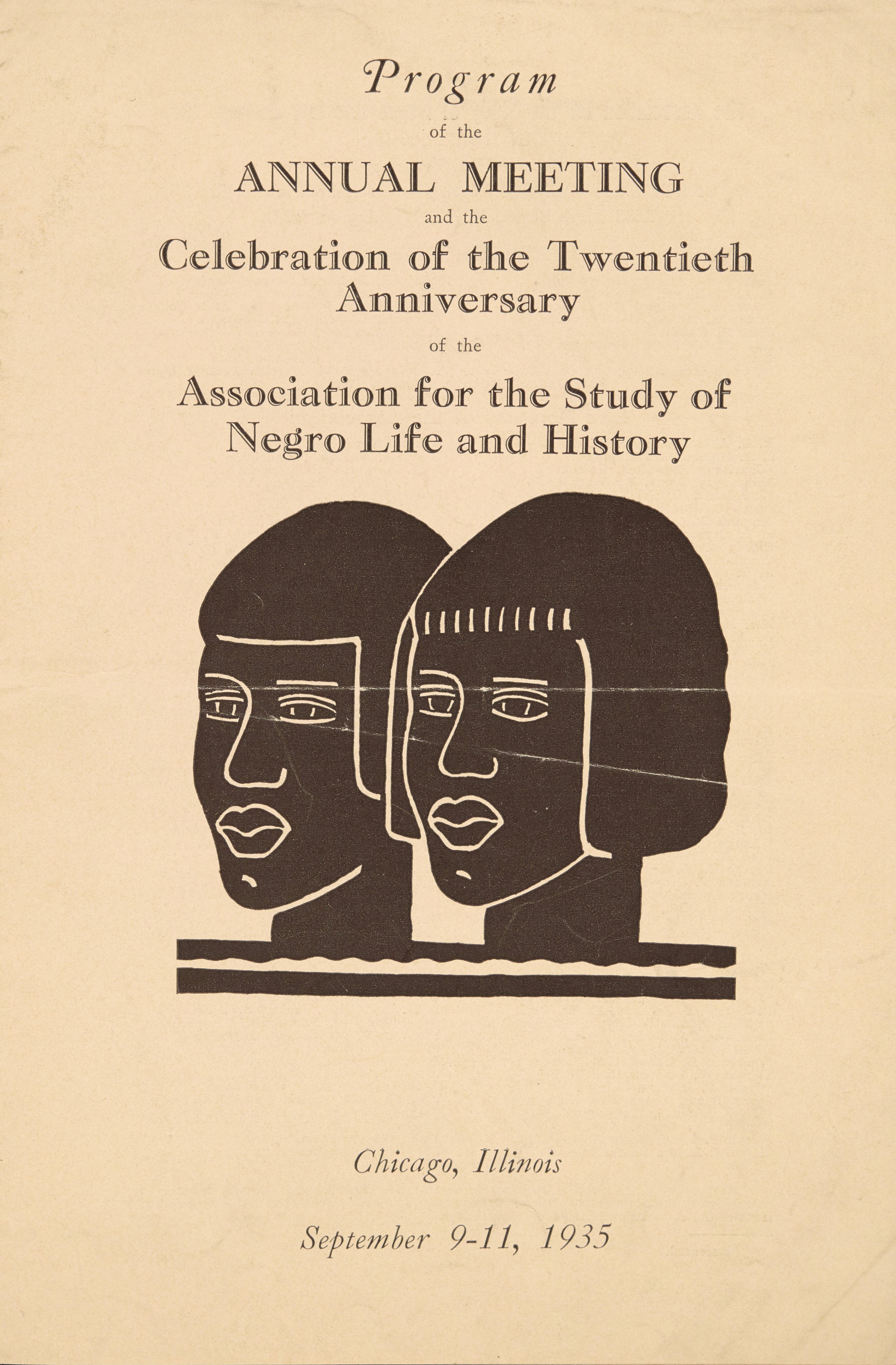

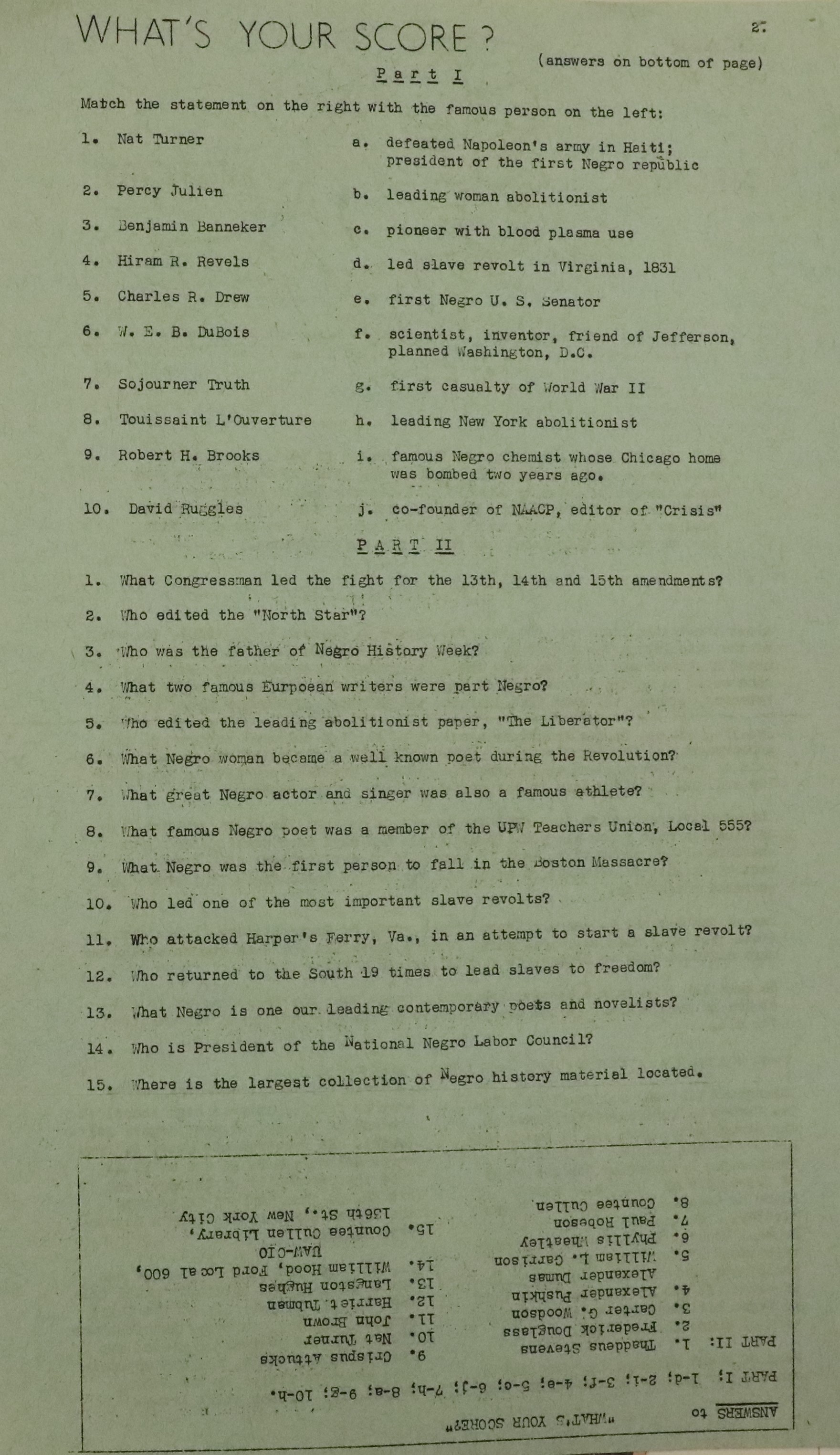

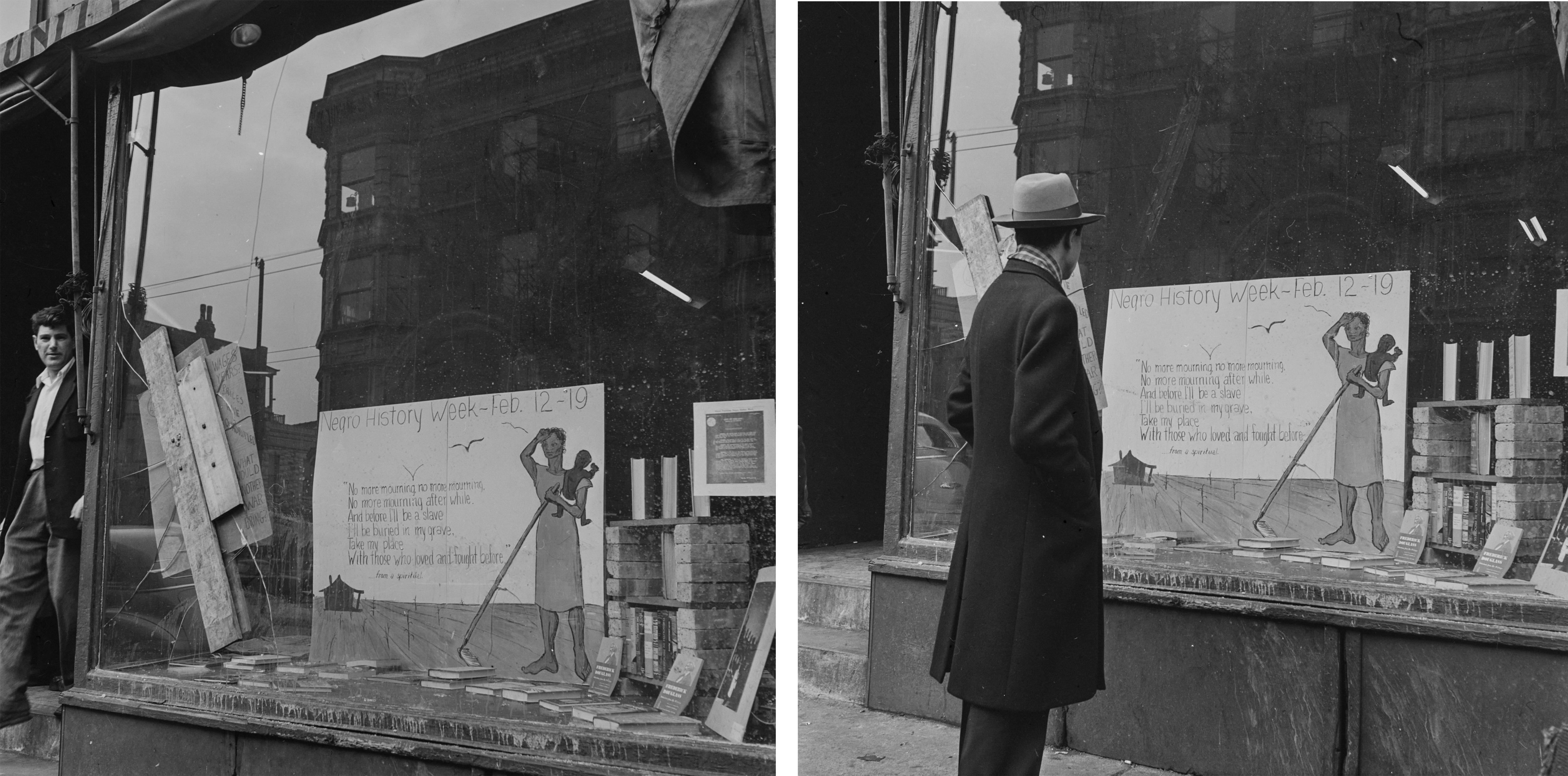

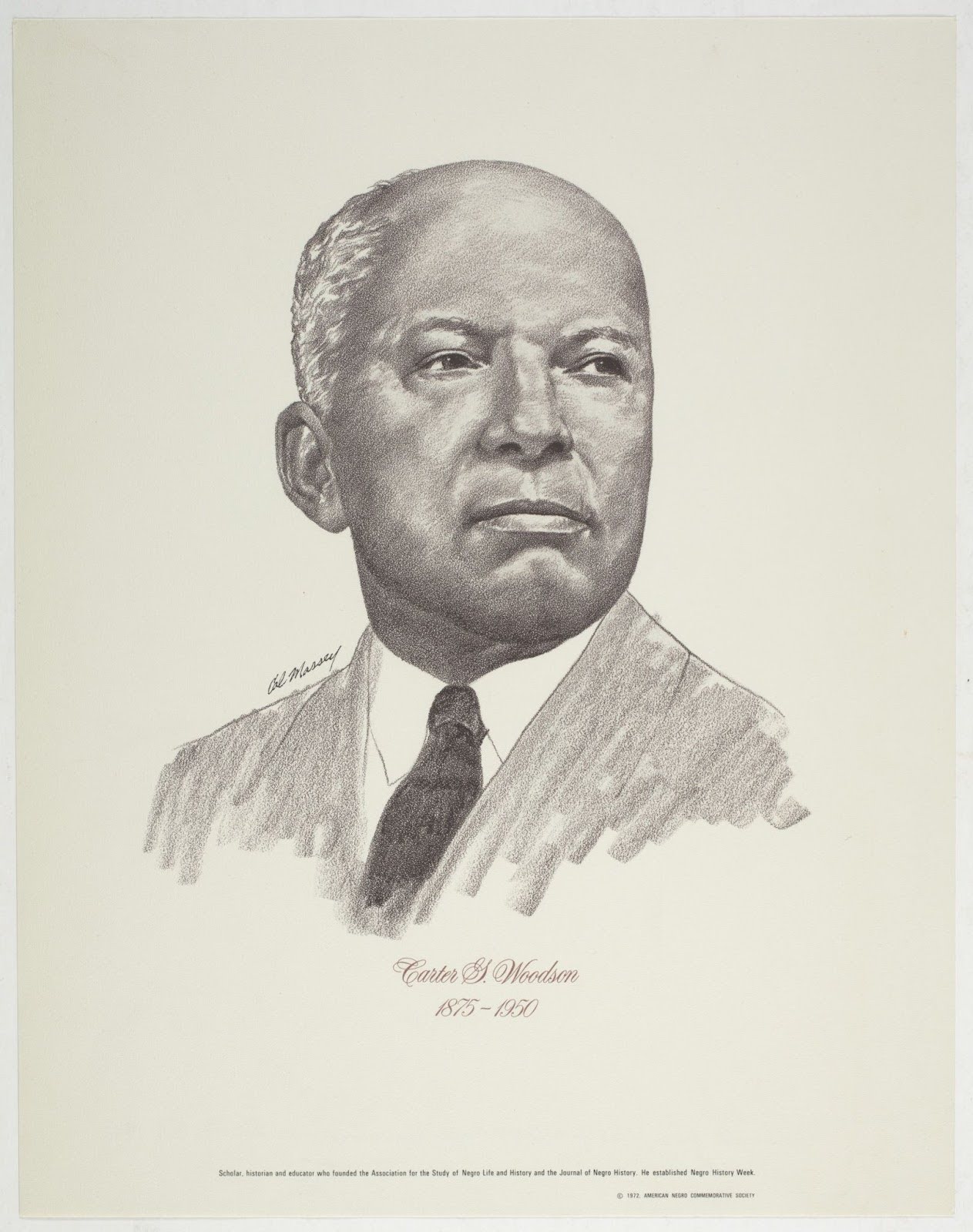

The origins begin at the historic Wabash YMCA in the Bronzeville neighborhood, where a renowned historian Carter G. Woodson came up with an idea that would eventually become the Black History Month we know today. But in the 1920s and ‘30s, he faced resistance from white people who felt threatened by the celebration and some Black leaders who were under pressure. Woodson’s defense of the commemoration holds nearly 100 years later.

The origins begin at the historic Wabash YMCA in the Bronzeville neighborhood, where a renowned historian Carter G. Woodson came up with an idea that would eventually become the Black History Month we know today. But in the 1920s and ‘30s, he faced resistance from white people who felt threatened by the celebration and some Black leaders who were under pressure. Woodson’s defense of the commemoration holds nearly 100 years later.

Erica Griffin-Fabicon is the director of education at the Chicago History Museum, and in her role, she works to help people better understand history connections.

Erica Griffin-Fabicon is the director of education at the Chicago History Museum, and in her role, she works to help people better understand history connections.

Griffin-Fabicon said Woodson’s defense of Black history can be applied to today. Woodson wrote in an editorial in 1932, “This celebration … is to be not so much a Negro history week as a history week,” and, “We have labeled the record of the Race as the history of this particular race because it has been omitted from the general histories.”

Griffin-Fabicon said Woodson’s defense of Black history can be applied to today. Woodson wrote in an editorial in 1932, “This celebration … is to be not so much a Negro history week as a history week,” and, “We have labeled the record of the Race as the history of this particular race because it has been omitted from the general histories.”

“But the problem was, Black Americans … could not be visible in the present and the past,” she said.

“But the problem was, Black Americans … could not be visible in the present and the past,” she said.

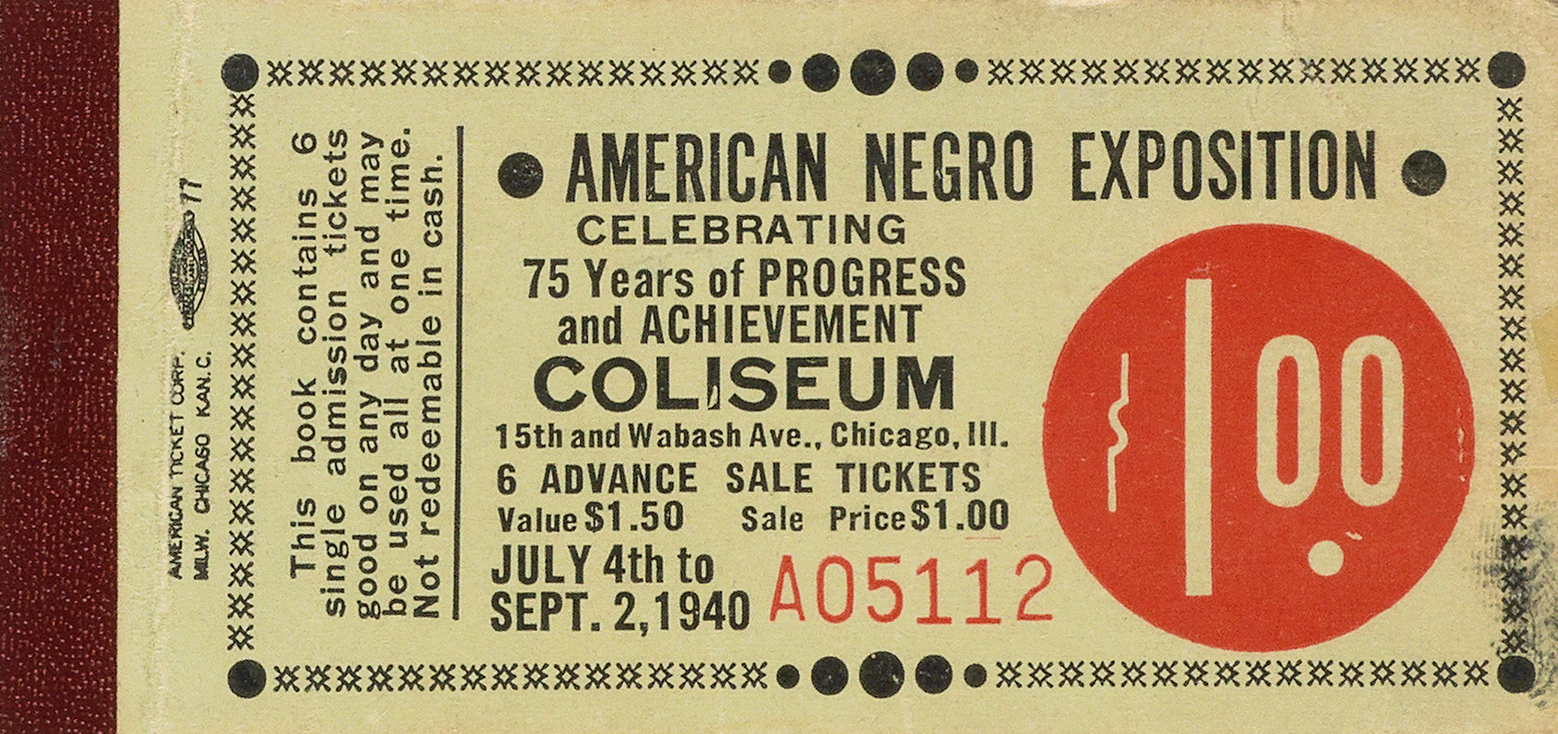

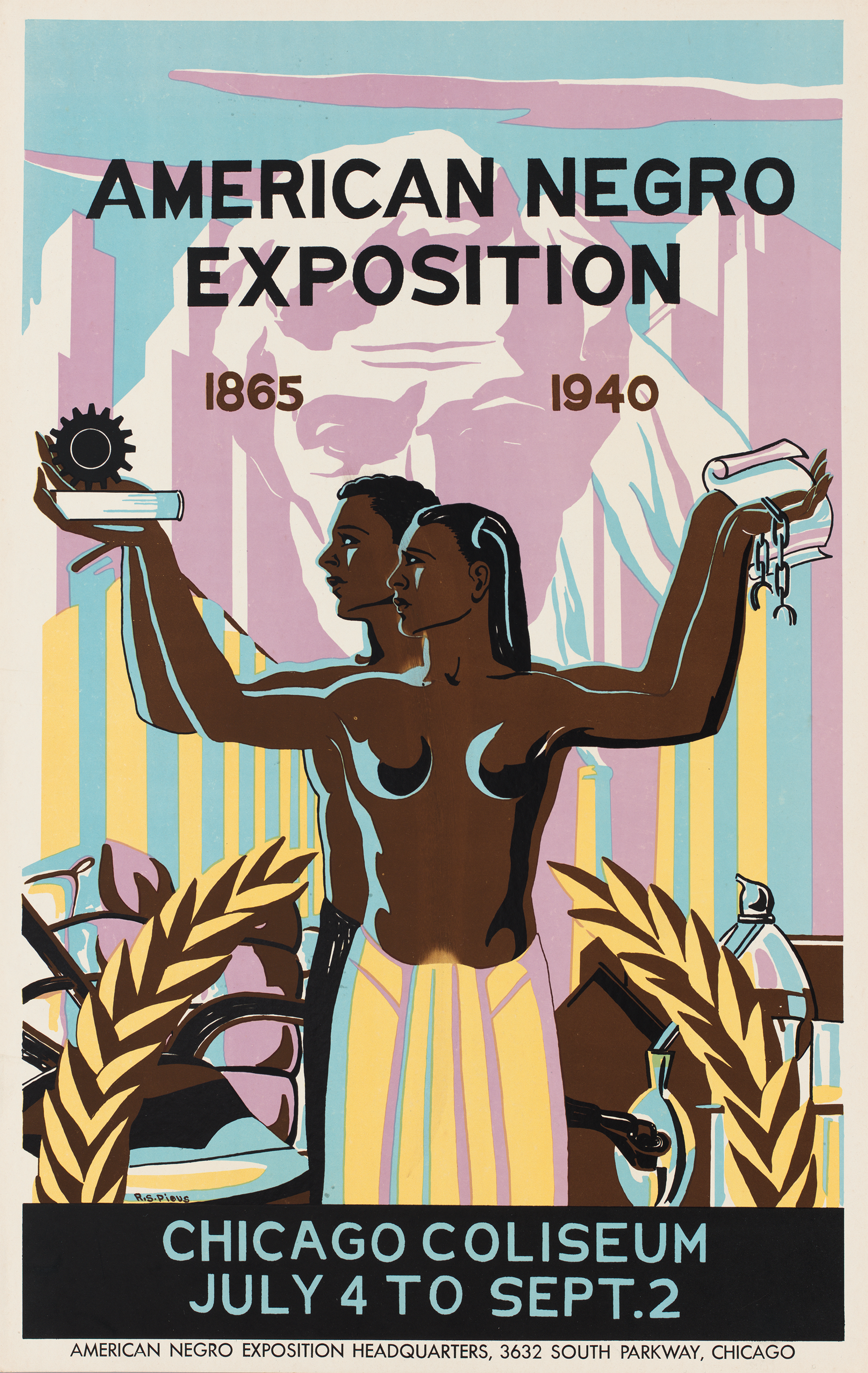

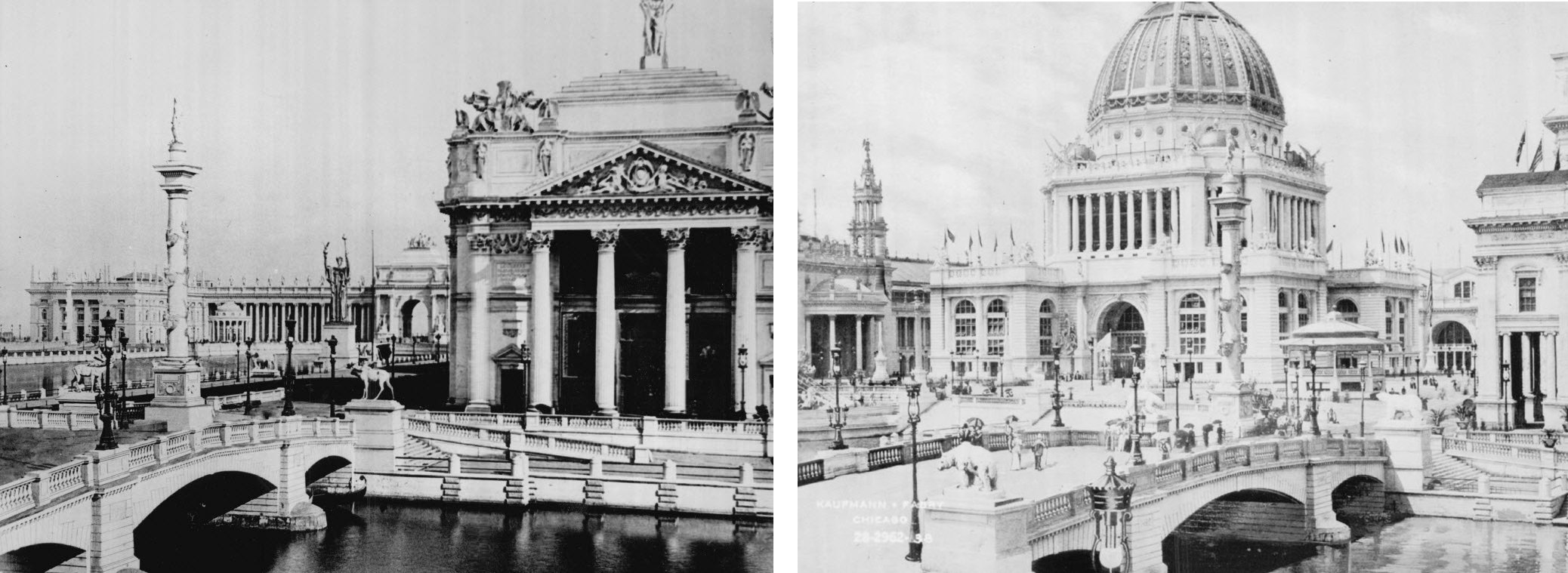

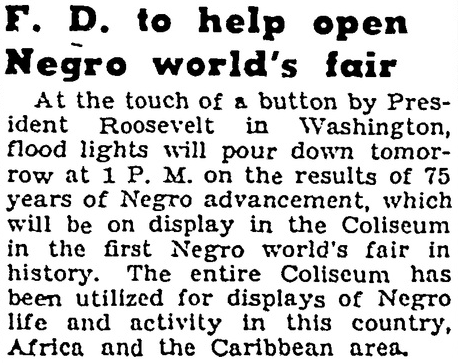

Government officials of all levels supported it, from Chicago Mayor Edward Kelly all the way to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. President Roosevelt himself pressed a button from his home in New York to turn on the lights at the Chicago Coliseum, where the exposition was located, launching the start of the two-month event.

Government officials of all levels supported it, from Chicago Mayor Edward Kelly all the way to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. President Roosevelt himself pressed a button from his home in New York to turn on the lights at the Chicago Coliseum, where the exposition was located, launching the start of the two-month event.

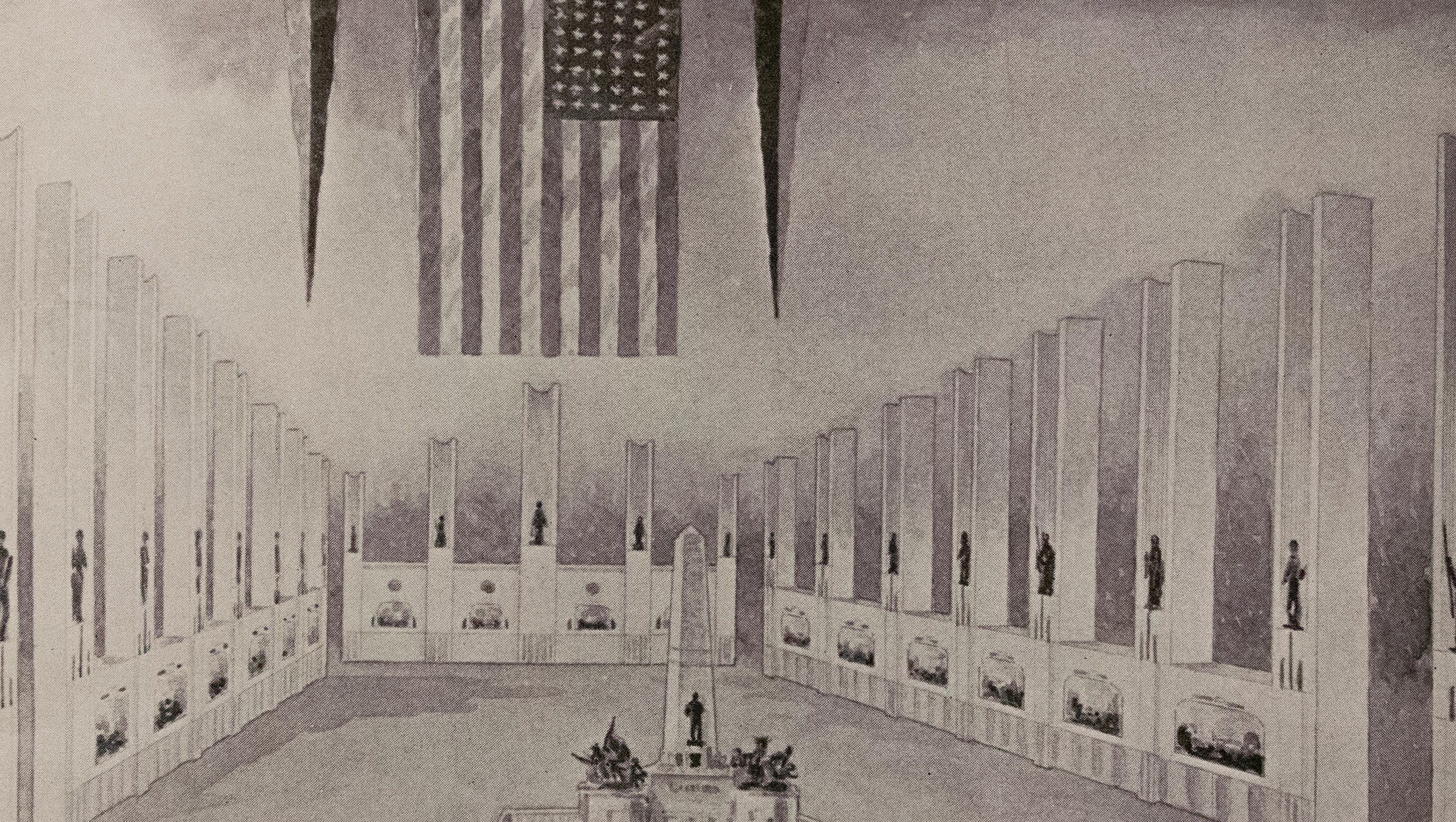

The Legacy Museum now has 20 dioramas on display. Dawson, along with exposition trustee Claude Barnett, were alumni of Tuskegee and gifted them to the university. However, they were in poor condition, and it took much work and care to restore each one. McGarity said it’s likely the remaining 13 are lost or destroyed.

The Legacy Museum now has 20 dioramas on display. Dawson, along with exposition trustee Claude Barnett, were alumni of Tuskegee and gifted them to the university. However, they were in poor condition, and it took much work and care to restore each one. McGarity said it’s likely the remaining 13 are lost or destroyed.

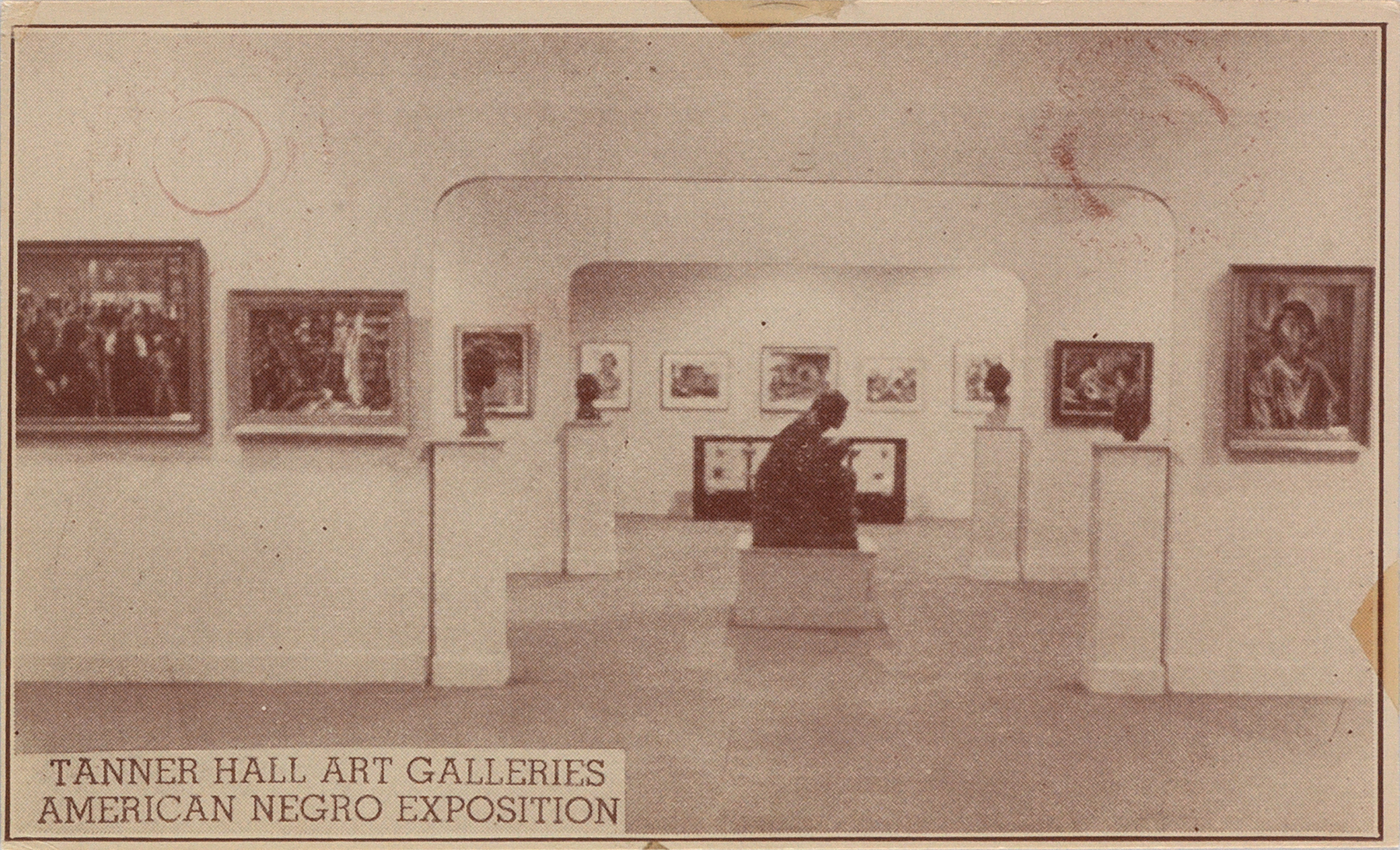

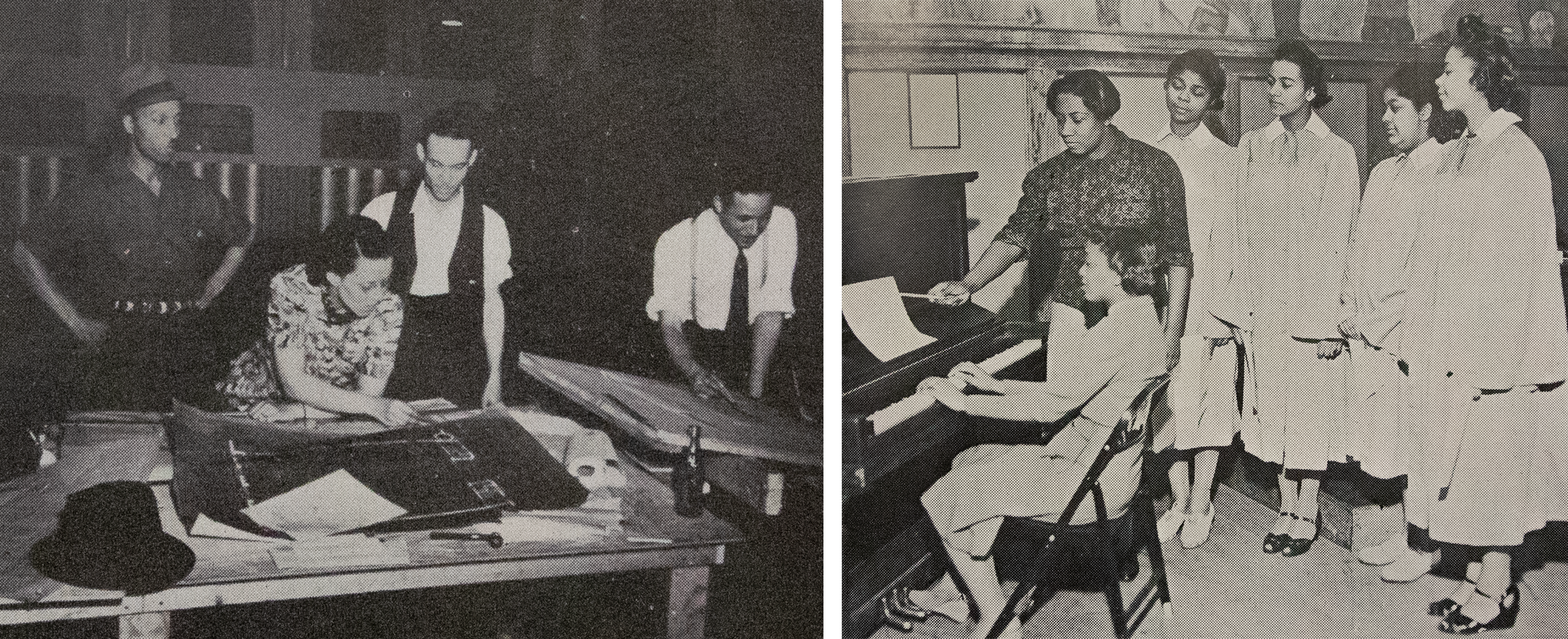

She explained the artists came together because they had no place to exhibit their work. They opened the center’s doors that December, just months after the exposition wrapped, creating a space of their own that would no longer be temporary. Its inaugural exhibition included work from artists like Charles White, Archibald Motley, Jr., Margaret Burroughs herself and so many more.

She explained the artists came together because they had no place to exhibit their work. They opened the center’s doors that December, just months after the exposition wrapped, creating a space of their own that would no longer be temporary. Its inaugural exhibition included work from artists like Charles White, Archibald Motley, Jr., Margaret Burroughs herself and so many more.

“When we first came in, no one wanted this place,” he said. “Even the members were like, ‘No, we’re gonna look somewhere else.’ I said, ‘This is where God wants us to be.’”

“When we first came in, no one wanted this place,” he said. “Even the members were like, ‘No, we’re gonna look somewhere else.’ I said, ‘This is where God wants us to be.’”

Others were removed by the city, which gets rid of newspaper boxes it deems abandoned or obstructing a public way, according to the municipal code.

Others were removed by the city, which gets rid of newspaper boxes it deems abandoned or obstructing a public way, according to the municipal code.

Curious City listener Amy Loriaux says she made lasting memories on the park’s playground as a child. But as an adult, Loriaux began to wonder how the park got its name.

Curious City listener Amy Loriaux says she made lasting memories on the park’s playground as a child. But as an adult, Loriaux began to wonder how the park got its name.

Elsewhere in Chicago, similar flawed depictions of Indigenous people were underway. U.S. post offices in the Chicago area

Elsewhere in Chicago, similar flawed depictions of Indigenous people were underway. U.S. post offices in the Chicago area

When Kristin Kutzner Huzar, a teacher from suburban Evanston and a single mother of two, heard about Kevin and his family through a volunteer group, she

When Kristin Kutzner Huzar, a teacher from suburban Evanston and a single mother of two, heard about Kevin and his family through a volunteer group, she

One of the most beloved figures at Tania’s was Orestes, the maître d' and waiter. Crowds would form around him and whoever he was dancing with — often Martha — to admire his salsa and merengue moves.

One of the most beloved figures at Tania’s was Orestes, the maître d' and waiter. Crowds would form around him and whoever he was dancing with — often Martha — to admire his salsa and merengue moves.

“I remember that somebody came up with this poem, kind of a refrain,” said Carlos Eire. “Adiós, Chicago querido. Tierra de frío y trabajo. Aquí dejo mi abrigo, y me voy para carajo. Goodbye, Chicago, land of cold and work. I leave you my coat. And I go to hell.”

“I remember that somebody came up with this poem, kind of a refrain,” said Carlos Eire. “Adiós, Chicago querido. Tierra de frío y trabajo. Aquí dejo mi abrigo, y me voy para carajo. Goodbye, Chicago, land of cold and work. I leave you my coat. And I go to hell.”