Flooded basements are becoming more common in Chicago. Here’s what you (and city officials) can do.

Chicago was built along a maze of rivers and marshy wetlands, and flooding has been an issue since Day One. Over the years, engineers have dreamt up some big, ambitious schemes to keep the water confined to our rivers and lakes and out of our streets and homes: they raised buildings to lay the original sewer pipes, reversed the flow of the Chicago River to protect our source of drinking water, and in 1975, began construction on the Tunnel and Reservoir Plan to capture excess water during heavy rains.

And still we flood. The sewer system gets overwhelmed after just two-thirds of an inch of rainfall in an hour, according to modeling by the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District (MWRD), the regional agency responsible for managing stormwater and cleaning wastewater.

It’s an all-too-familiar scene: Chicago gets hit with fast, heavy rain, and then the city is left with sewage backup and flooded basements. It’s a costly headache for residents and the city, and over the years, it’s gotten many Curious City listeners wondering why this happens so often and what can be done about it.

We’ve created this resource to answer some common questions about flooding in Chicago and empower residents with the information needed to help protect their homes, their communities, our waterways and our city.

Why basements flood | Deep Tunnel | Chicago Harbor Lock | What government's doing | What government could do | Protecting my basement | Steps to take

How and why does sewage get into basements?

Most of Chicago’s sewer system was constructed before 1930, and like many older cities we have what’s called a combined sewer system. That means any rain or runoff that heads into the gutters in the street goes into the same pipes as anything we flush down the toilets or pour down our drains. In dry weather, that works just fine. But when it pours, there’s just too much water heading into those pipes at the same time and it creates a kind of gridlock.

Patrick Jensen, Senior Civil Engineer at the MWRD, said it’s a lot like pouring a giant pail of water into a small kitchen sink. “That sink is going to overflow, not necessarily because the drain isn't working, [but because] it simply cannot handle that flow in that fast amount of time to prevent it from overtopping.”

When that happens, pressure builds in the pipes, pushing in every direction — including backwards, into basements. Any water flushed down the toilet or down the drain also has a hard time leaving and will likely back up into the house.

Beyond the design of our sewer system, there are two key reasons this is happening more often in recent years: First, our built environment has covered up most of the grass and soil that might otherwise absorb stormwater into the ground. Second, heavy storm events are happening with greater frequency — and that is expected to become the norm rather than the exception as our climate continues to change.

I thought Deep Tunnel was supposed to stop flooding in the area. What gives?

The Tunnel and Reservoir Plan, commonly referred to as Deep Tunnel, is designed to provide a holding place for excess water when our sewer system is overwhelmed. It consists of 110 miles of giant tunnels that lie below city sewer systems throughout Cook County, ready to capture and carry away excess water to one of three massive reservoirs, where it is held until the water treatment plants have a chance to catch up.

The reservoirs can currently hold more than 11 billion gallons of water. But in July 2023, one of them — the McCook Reservoir — filled to capacity. To increase capacity by 6.5 billion gallons, crews are currently blasting through rock and creating a fourth reservoir, set to be finished by 2029. In total, Deep Tunnel has been under construction for almost 50 years.

But here’s the catch: While Deep Tunnel helps hold excess water, it’s up to local municipalities to get the water from their sewer systems into the tunnels. That means it’s the responsibility of the Chicago Department of Water Management and its suburban counterparts to keep their sewers clear and functional. “And that's the biggest problem we have,” said Dick Lanyon, retired executive director of the MWRD. “The sewers have to be maintained, periodically inspected by closed circuit TV cameras, cleaned, [and] any failures have to be repaired.”

Things like leaves and debris can block pipes, and sometimes they cave in after years of use. While the top engineer at the MWRD said the rule of thumb is to inspect sewer lines every five years or so, depending on how often an area experiences issues, the Chicago Department of Water Management Deputy Managing Commissioner Matt Quinn said his crews make their way through each neighborhood about once every 10 to 15 years. Other than that they respond to problems when people file complaints and inspection requests with 311. (Our public records request found that the DWM doesn’t keep centralized records of when and where it inspects sewer mains and structures, so it’s hard to say with certainty how often they’re checked, on average.)

Does opening the locks reduce basement flooding?

The Chicago Harbor Lock is located near Navy Pier between Lake Michigan and the mouth of the Chicago River. During heavy storms, the MWRD can open gates at the lock after the river rises above the level of the lake to reduce flooding along the river banks by temporarily allowing water to flow towards the lake.

However, doing so pollutes Lake Michigan, our source of drinking water. Plus, it doesn’t actually do anything to reduce basement flooding, according to Lanyon. “Even if you could open the locks earlier,” Lanyon explained, “the water has to go such a distance to get to the lakefront — and through all the sewers and canals — that [it’s] not a solution at all.” Extraordinary rain events overwhelm the city’s system, period — regardless of whether the gates and lock are open or not.

What are local leaders and agencies doing to deal with this?

There are two main agencies responsible for the sewer system in Chicago and the surrounding area. The Metropolitan Water Reclamation District (MWRD) is the regional stormwater management authority that cleans wastewater and releases it back into area waterways. They also own and manage Deep Tunnel, designed to reduce pressure on the system, and thus the amount of sewage and rainwater runoff released into those waterways during heavy storms. The Chicago Department of Water Management (DWM) manages about 4,500 miles of sewer pipes running under city streets and delivers drinking water to Chicagoans. The two agencies have several initiatives aimed at improving the function of and reducing pressure on the system during heavy rains.

Replace and repair sewer mains: In the past decade, the DWM has lined or replaced more than 750 miles of sewer mains as part of an infrastructure improvement project that kicked off during Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s administration. This is a great start — but it accounts for just 17% of the system. Moving forward, the work will continue at a pace determined by funding, with the department prioritizing older sewer lines and those that hydraulic modeling suggests might be problem areas, often because they are too narrow for modern rain events.

Install water restrictor valves: Restrictor valves, or ‘rain blockers,’ are barriers that attach to storm drains and act as funnels, controlling the flow of water into sewers during heavy rains. The DWM has installed restrictor valves on most Chicago streets — which makes them act as temporary retention pools when the sewer mains get overwhelmed. According to the DWM, “water in the street is better than water in the basement.” However, they say, residents don’t always see it that way and sometimes remove restrictor valves to avoid having flooded streets.

Create green infrastructure: In the past decade, the DWM has partnered with the MWRD, Chicago Public Schools and other organizations to rip up large swaths of impervious pavement on more than 30 schoolyards and replace them with permeable pavement, vegetation and other stormwater retention features. The MWRD has also been investing heavily in green infrastructure and rainwater management. In partnership with local municipalities, they currently have more than 220 green infrastructure and flood resiliency projects in some phase of planning or construction as part of their Green Infrastructure Partnership Program.

Increase capacity: DWM Commissioner Dr. Andrea Cheng said the DWM is also designing and seeking funding for additional large-scale tunnels that would help get Chicago’s sewer and stormwater to the MWRD’s Deep Tunnel system more quickly. It’s unclear what the timeline for the project will be.

Educate and provide resources to residents: The MWRD has a number of resources available for homeowners interested in learning more about protecting their home and reducing their contribution to regional flooding problems. The agency also sells and delivers discounted rain barrels to Cook County residents.

What more could the city be doing?

Over the years, city leaders have put out several well-researched plans to try to tackle this issue comprehensively. (See Daley’s plan for Green Urban Design and Climate Action Plan, Emmanuel’s Green Stormwater Infrastructure Strategy, Lightfoot’s Climate Action Plan.)

But none of those plans have been executed in any meaningful or comprehensive way.

However, there are other cities that are finding solutions and can provide a model for regional leaders. Here are just a few of the lessons and efforts local experts are calling for:

Create a centralized plan: “Milwaukee has made really clear plans, has a clear vision and has put in place millions of gallons worth of stormwater storage with green infrastructure,” said Nicole Chavas, president of Greenprint Partners, a sustainable planning and engineering firm based in Chicago. The city’s Environmental Collaboration Office acts as a hub for promoting and coordinating sustainability efforts across government agencies and communities. Chicago’s Department of the Environment, with a similar mandate, was dismantled by Mayor Rahm Emanuel in 2012 — though it could be re-established under Mayor Brandon Johnson.

Provide government assistance for flood mitigation: Several suburban communities — including Wheaton, Oak Park and Morton Grove — offer rebates, cost-sharing options or grants to help residents install flood mitigation retrofits such as check valves, overhead sewer lines or even green infrastructure on their property. “I do think that a lot of the federal funding that's coming down the pipe is eligible and could be used to implement grant programs to support homeowners,” said Chavas.

Send emergency alerts during heavy rains: Professor Rachel Havrelock from the University of Illinois at Chicago’s Fresh Water Lab said our region should have mass alert notifications that encourage people to adjust their behavior during heavy rain events. The MWRD already has an opt-in text notification, but Havrelock said these ought to be similar to the air quality alerts over the summer that were impossible to ignore. “People need to hold their household water use when it is raining,” she said at the recent City Council hearing. “Anybody in an area that's flooding, their phone should light and buzz … in conjunction with billboards [and] public service announcements for people to begin to understand that any water put into the system during a rain event can resurface in your household. ”

How can I keep water out of my basement?

If you own your home, you have a few options to reduce the likelihood of sewage backing up into your basement during heavy rains, particularly for older buildings. (If you rent, there are some resources for renters whose apartments flood.) These solutions tend to be costly — and they make things worse for people on your block that do not have flood control mechanisms because they result in more pressure on the system. Still, when faced with a flooded basement, those who can afford to may choose to install some upgrades. Here are some of the most popular options in the Chicago area:

Install a check valve: Check or backflow valves are installed into the private sewer pipe, usually by digging a pit in the front yard, to make sure wastewater can only flow out and cannot back up from the public main.

Cost: Typically between $5-8,000.

Caveats: In the event of a heavy storm, a check valve might not be able to allow any sewage to leave the home, meaning you have to be careful not to flush or pour anything down your pipes. They also require regular inspections to make sure they don’t get stuck.

Construct an overhead sewer line: This is a major reconstruction of your internal plumbing system that pumps wastewater from basement facilities (like your washer and any bathroom you might have in the basement) to a pipe in the basement ceiling or first floor, sending it out of the house from there. The higher elevation means that it’s less likely your pipes will back up, unless flooding outside reaches above the level of the pipe.

Cost: Between $15 and $25,000, depending on how much reconstruction is needed.

Caveats: None, outside of the cost.

Use a standpipe: A standpipe is basically a big PVC pipe that is sealed to the sewer drain in your floor. It’s used to raise the lowest drain opening in the home to a level that is higher than the sewer, making sewage backup into the home less likely.

Cost: Around $30.

Caveats: This is only useful when all you’re getting is a small amount of backflow coming from the floor drain (otherwise the water will likely find its way in through other openings in your home). Plus, sometimes the seals crack and need to be replaced.

The above projects only help prevent sewage backups. If you also experience seepage during heavy rains, you might want to explore installing drain tiles, waterproofing or sealing cracks in the foundation.

You can also ask the city to inspect your sewer if you suspect there may be a larger problem.

How can I reduce pressure on the sewer system?

There are several small-to-medium lifts that can greatly reduce your contribution to the sewers during heavy rains, thus improving outcomes for you and your neighbors. They include:

Disconnect your downspouts: Chicago city code used to require downspouts carrying water from our roofs feed directly into the sewer, which added a lot of unnecessary pressure on the system during heavy rains. According to the MWRD, a house with a roof that is 800 square feet can send about 500 gallons of water to the sewer during a one-inch storm. And when the system gets overwhelmed, all of that water can come right back into your home. If you’re a homeowner and you haven’t done it yet, this guide from the MWRD can help you tackle the project.

Plant a rain garden — or at least native plants: Native plants provide myriad benefits to ecosystems and gardeners (they’re easier to keep alive and disease-free!). They also do a great job soaking up water from your yard or rain garden. Check out this guide from the MWRD to learn more about plants native to Cook County that are particularly adept at thriving in wet environments and returning stormwater to the ground, as nature intended.

Install a rain barrel: A rain barrel placed under a modified downspout can reduce your utility bill and help decrease the amount of stormwater you’re sending to the sewer. The MWRD sells rain barrels at a discount and has guidance for how to install and maintain them. (Pro tip: empty it before the first freeze and store it inside for the winter.)

Replace concrete and asphalt with permeable pavement: Unlike traditional paving that often directs stormwater directly into the sewer, permeable paving allows water to drain through and absorb into the ground. (It also is less likely to form a slippery coat of ice in the winter.) Design and construction can be more complicated, but there are guides to get you started.

Have your sewer line checked: The privately owned sewer pipes (also called “laterals”) that run from your home or building to the main under the street can cause you problems if there are tree roots, grease, or other blockages obstructing the pipe, preventing wastewater from leaving the house. You may also have issues if cracks or connections to other pipes are letting in additional water and causing them to exceed their capacity. Periodic private inspections from a certified plumber can help identify and resolve any issues.

File a request with 311: Whenever you have water in your basement or suspect a problem with your sewer line, notify the city online or over the phone. This helps them identify problem areas, measure the extent of the problem and plan future projects.

There are many excellent resources with more detail on how to do the above and much more. They include the MWRD’s Green Neighbor Guide, its Overflow Action Day text alerts and the Center for Neighborhood Technology’s RainReady Homeowner Guidance.

Jessica Pupovac is a Chicago-based reporter, producer and editor.

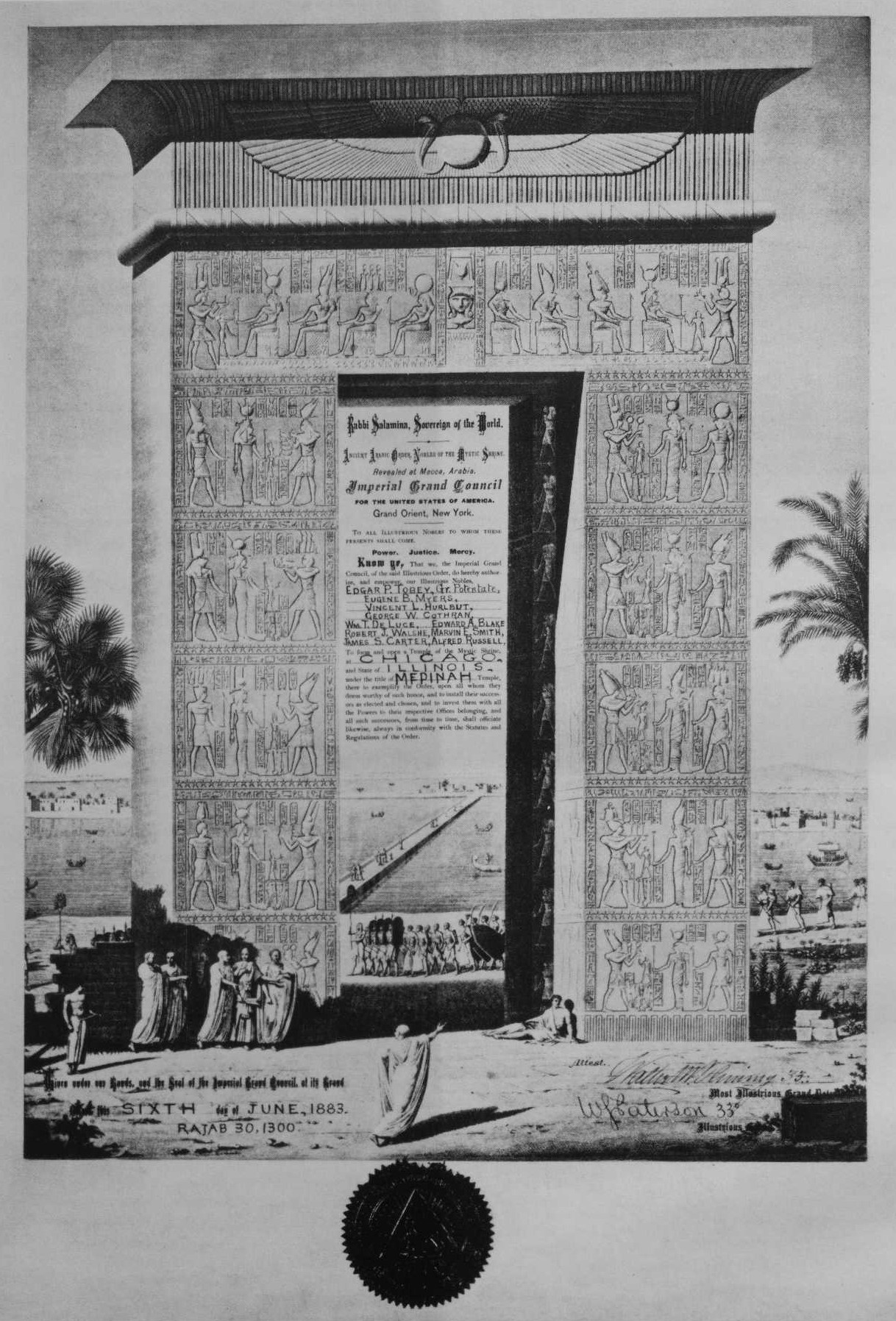

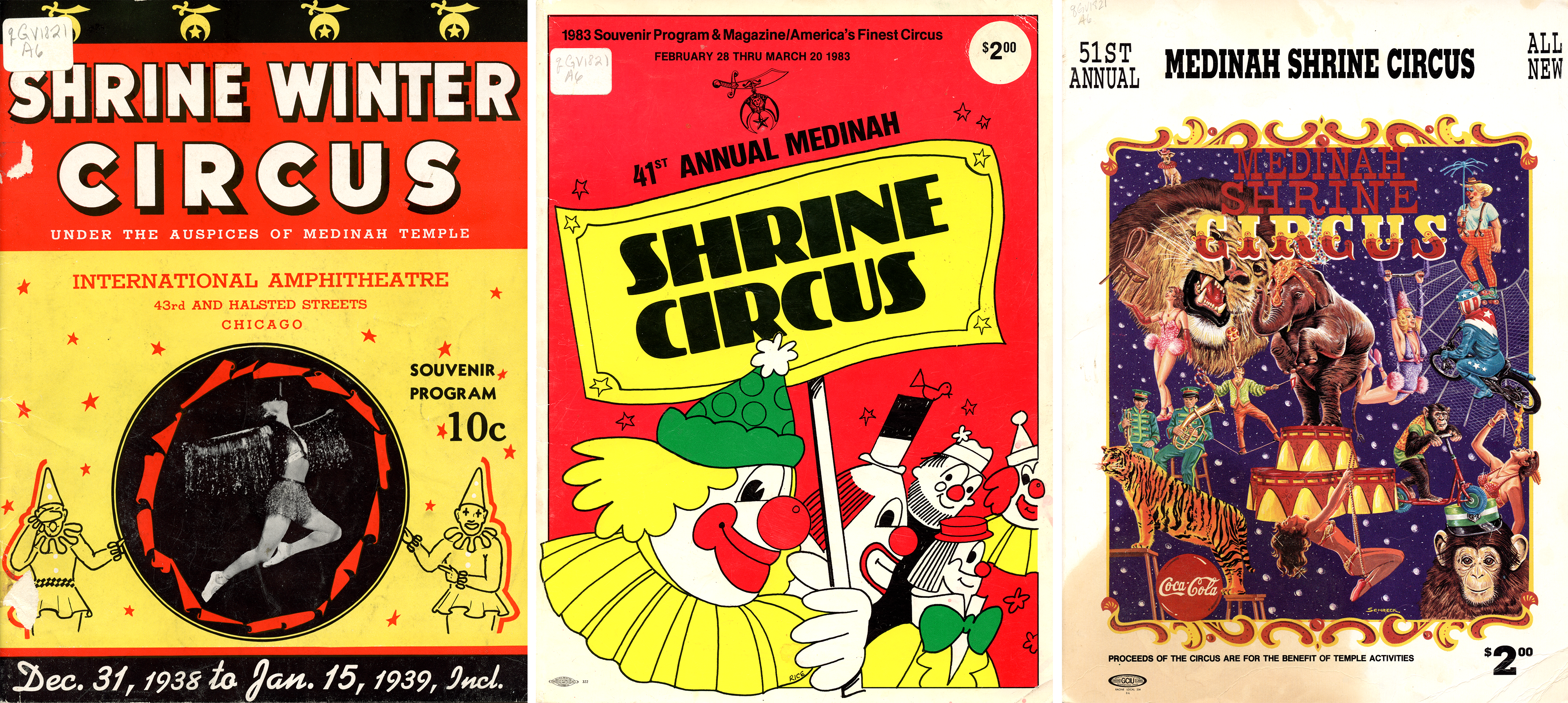

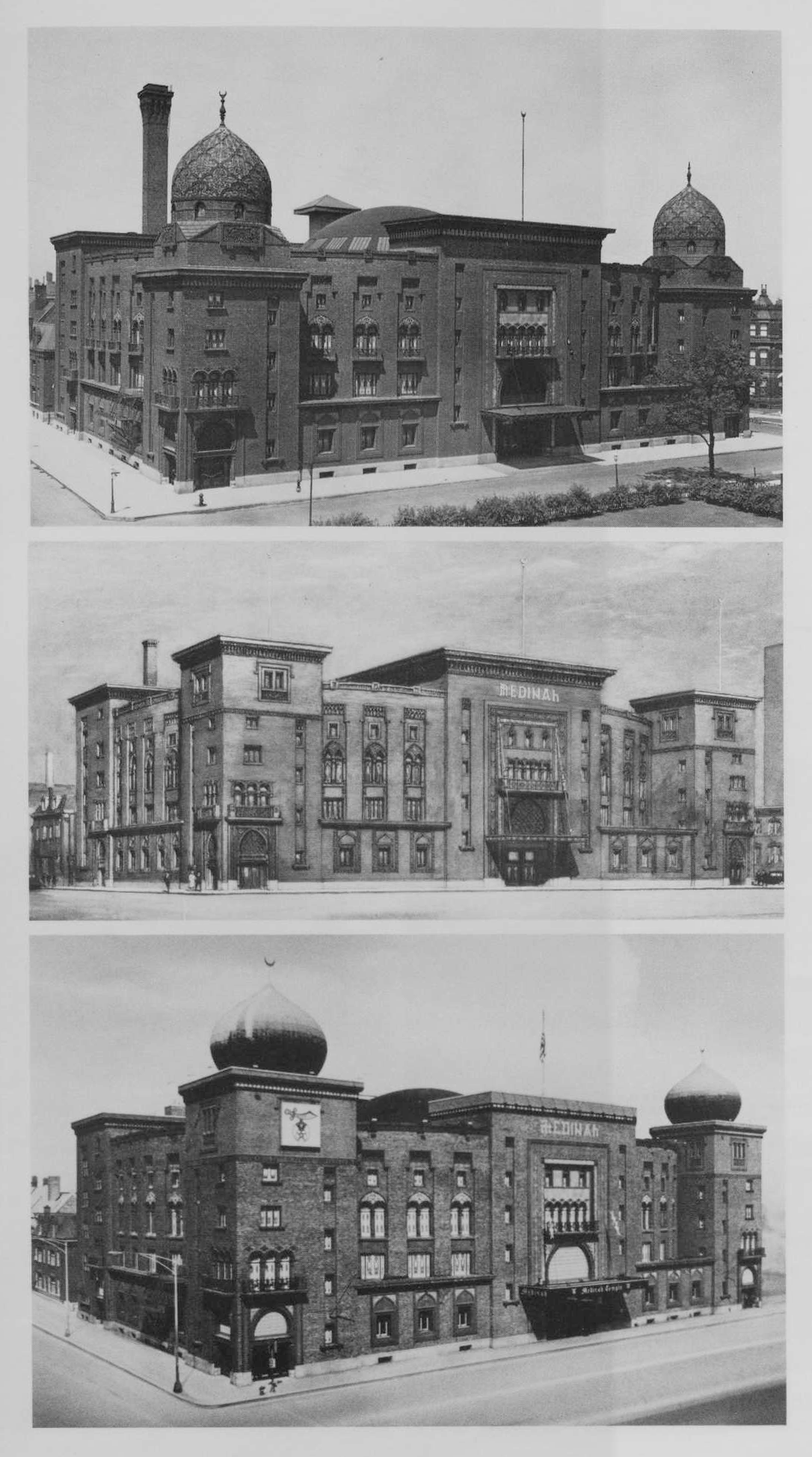

In 1870, a New York Freemason named William J. Florence returned from a trip to Cairo and Algiers and shared notes and drawings from his travels with another member of his fraternity, Walter M. Fleming. Fleming created a ritual incorporating symbols and motifs from Florence’s notes. Soon afterwards, according to the Shriners’ own historical accounts, the two men brought together a small group of Masons to create a new organization based loosely on the “glamour, pageantry and mystic splendor” Florence had seen during his travels. They called their fraternal order the Ancient Arabic Order of the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine.

In 1870, a New York Freemason named William J. Florence returned from a trip to Cairo and Algiers and shared notes and drawings from his travels with another member of his fraternity, Walter M. Fleming. Fleming created a ritual incorporating symbols and motifs from Florence’s notes. Soon afterwards, according to the Shriners’ own historical accounts, the two men brought together a small group of Masons to create a new organization based loosely on the “glamour, pageantry and mystic splendor” Florence had seen during his travels. They called their fraternal order the Ancient Arabic Order of the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine.

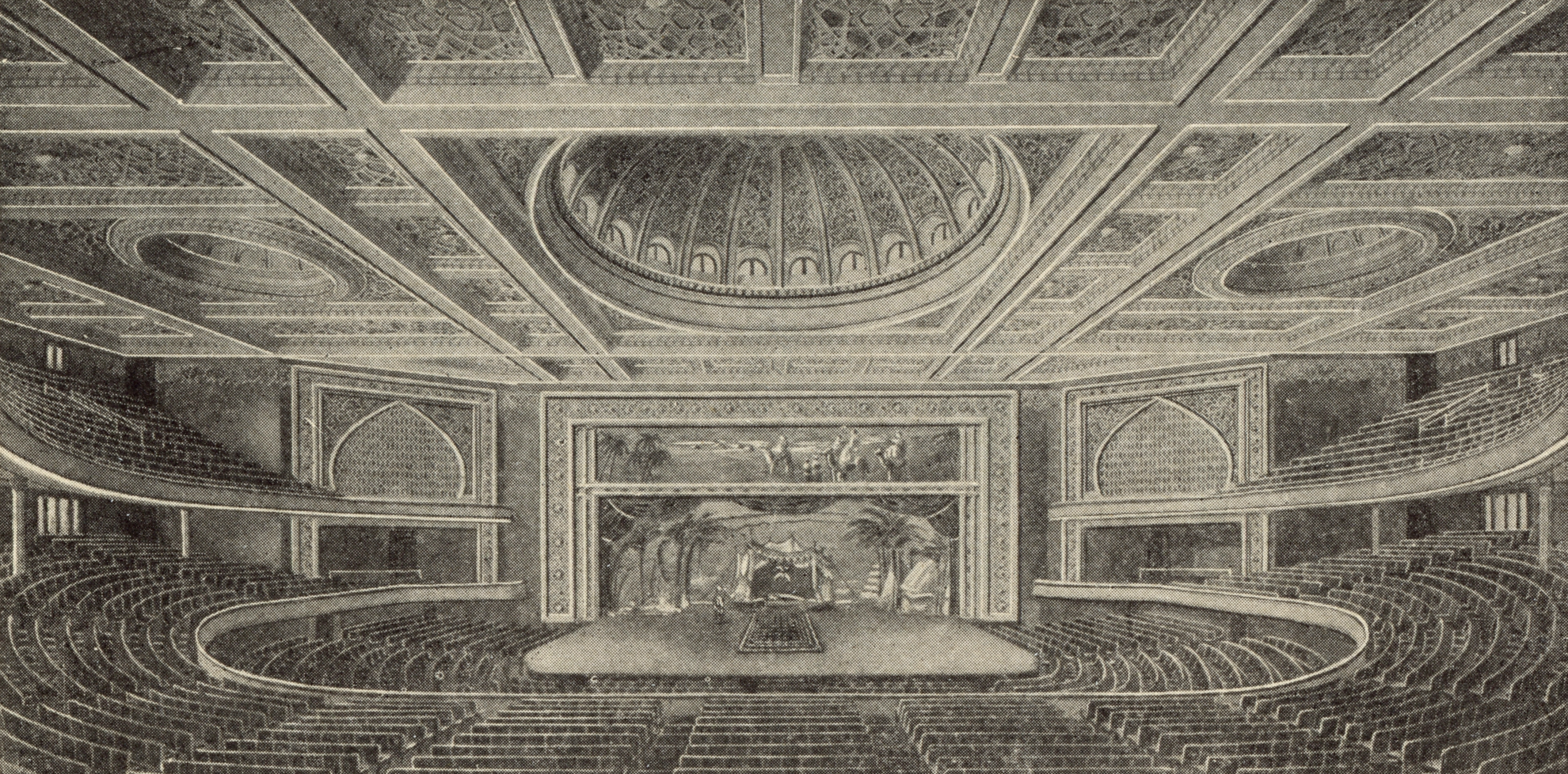

Shriners like Paul Barber joined the organization mostly to get involved in the musical performances that took place there.

Shriners like Paul Barber joined the organization mostly to get involved in the musical performances that took place there.

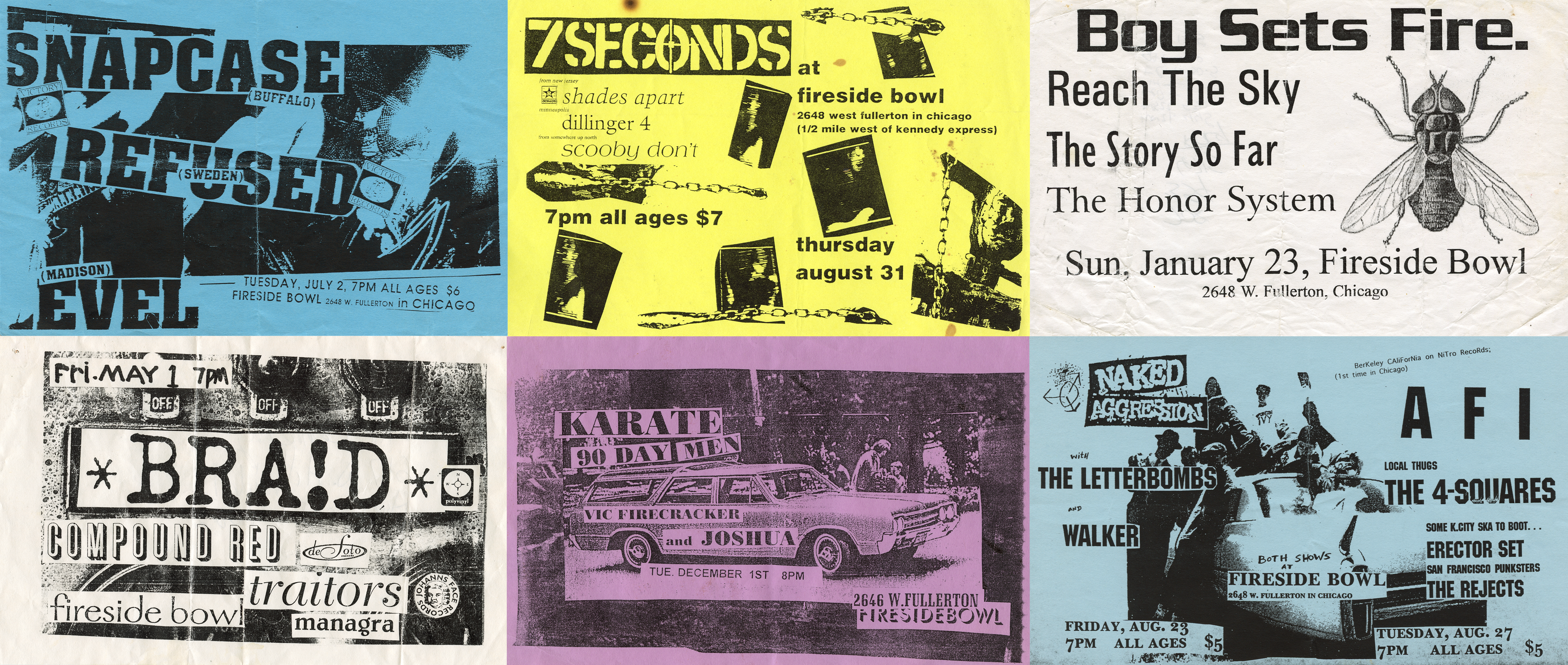

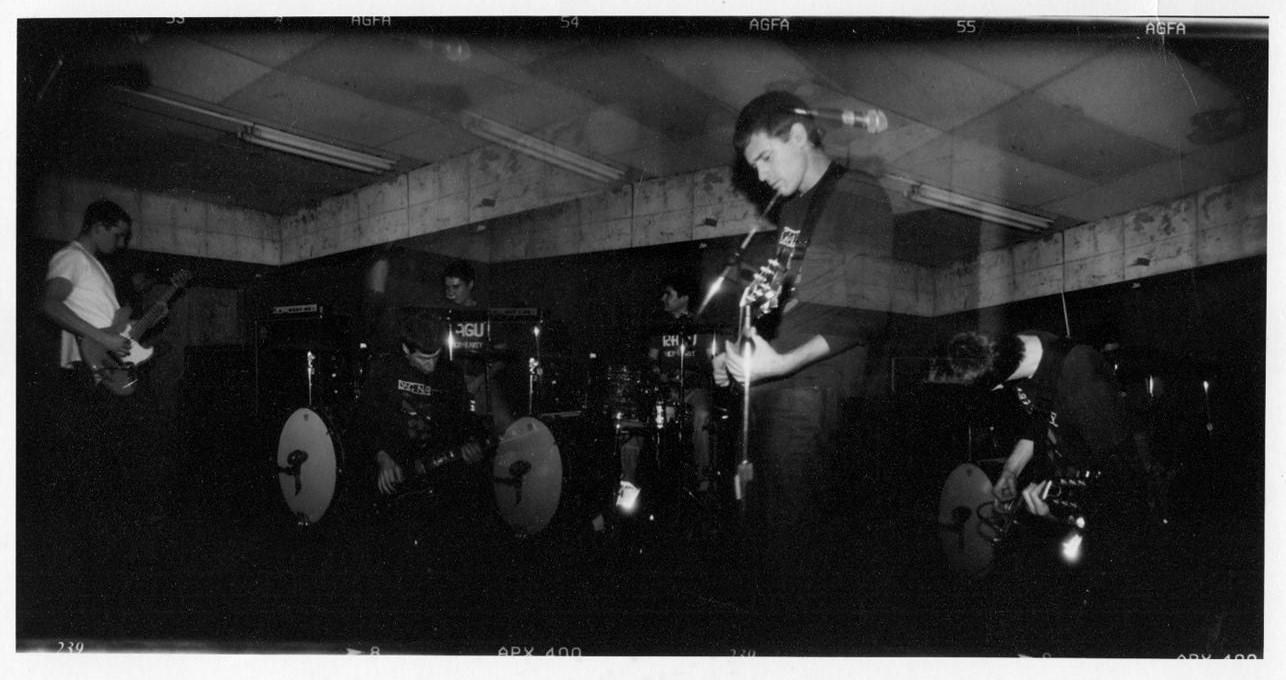

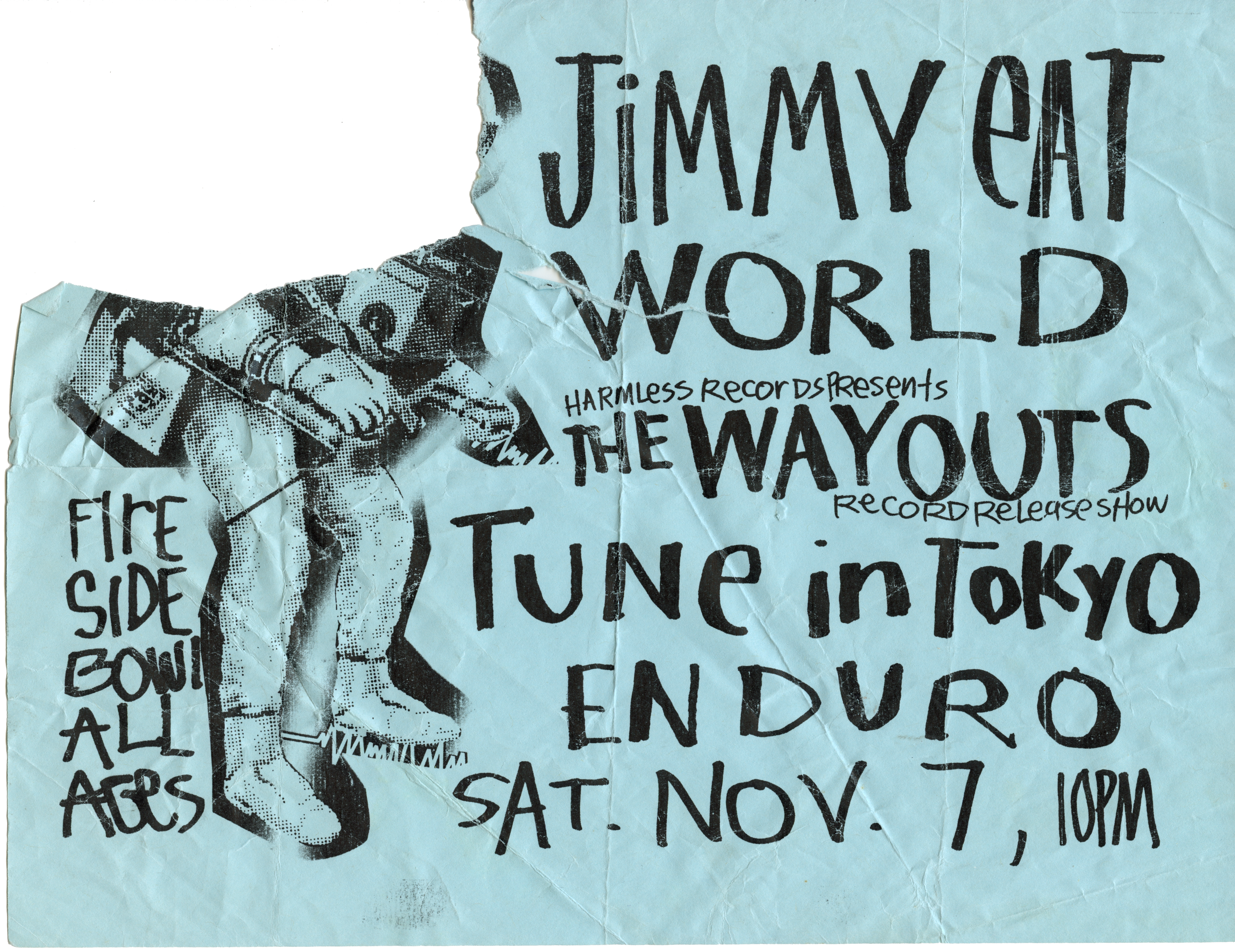

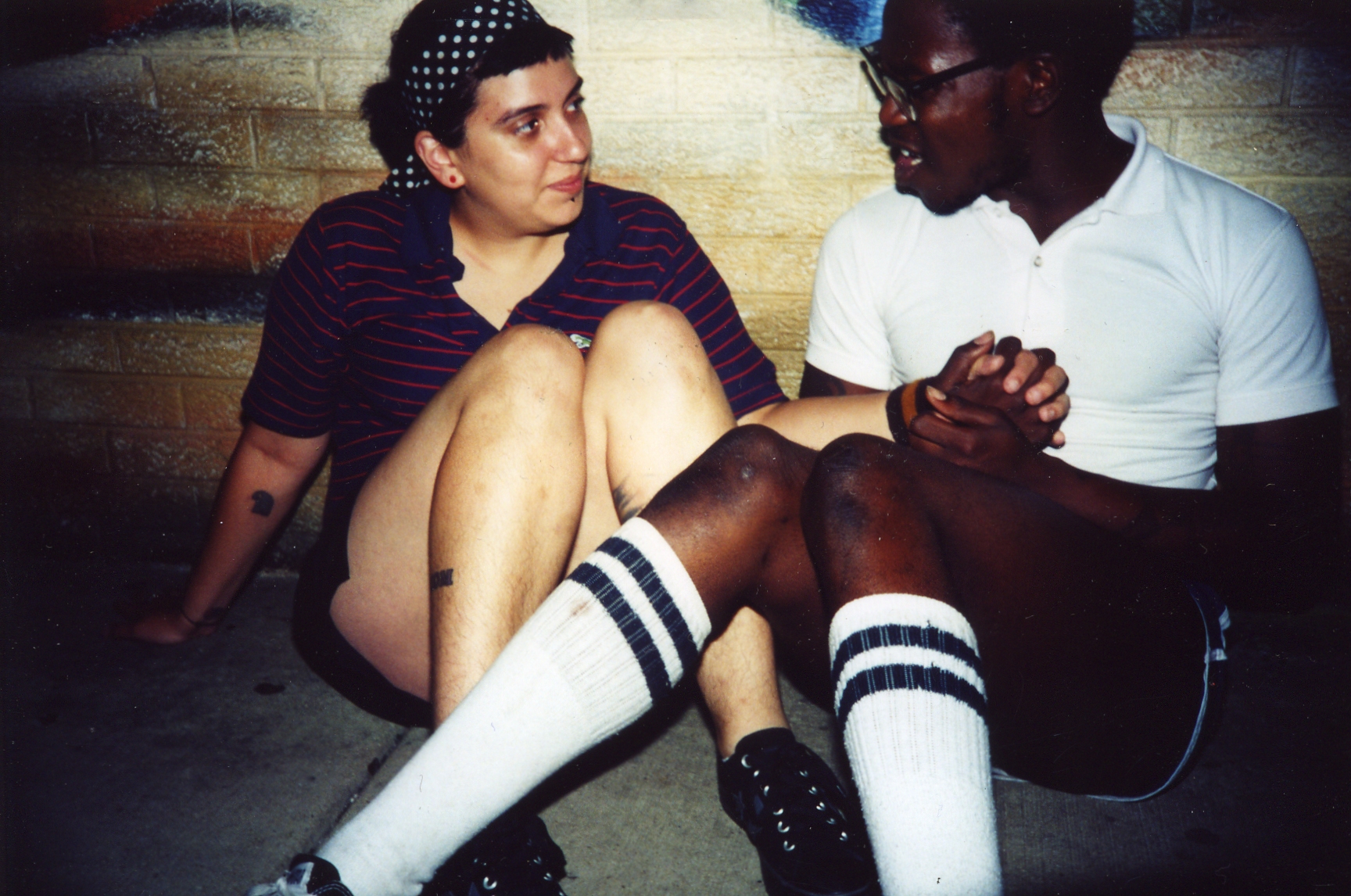

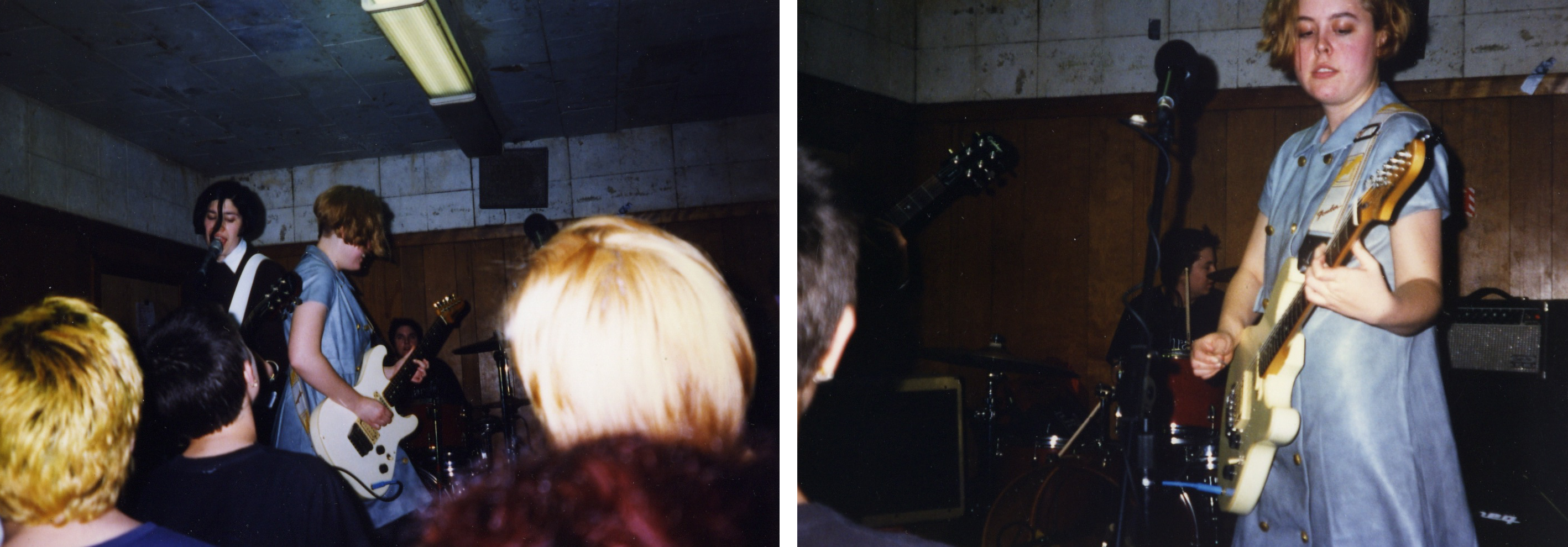

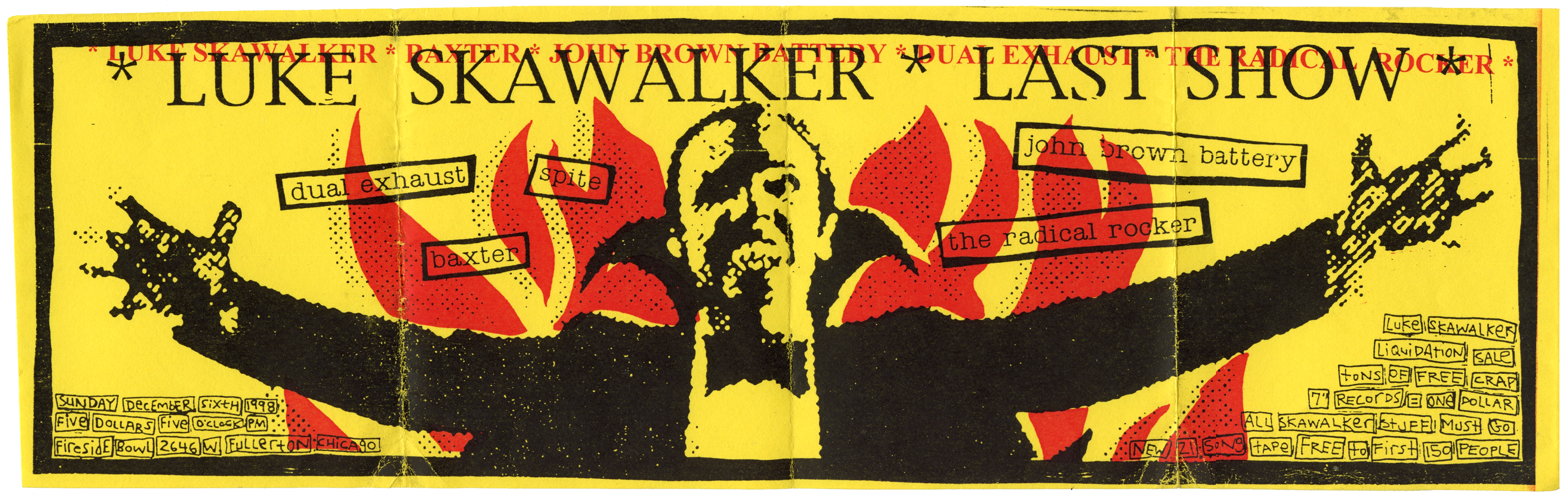

And Chicago’s indie scene was on the rise, too. Punk rock bands like 88 Fingers Louie and Smoking Popes had developed cult followings.

And Chicago’s indie scene was on the rise, too. Punk rock bands like 88 Fingers Louie and Smoking Popes had developed cult followings.

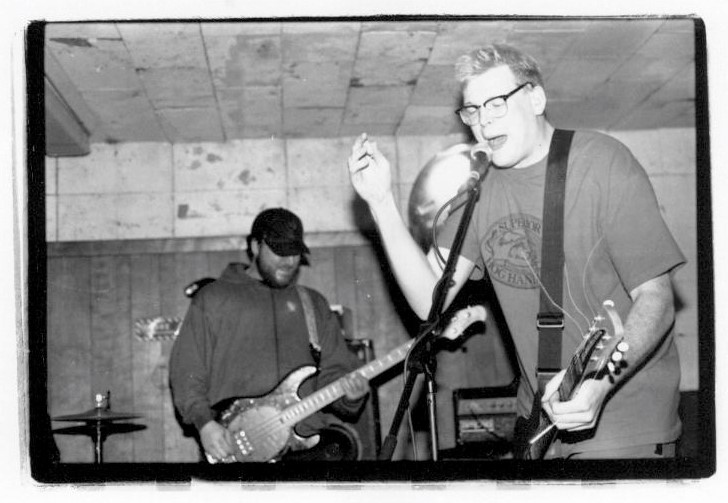

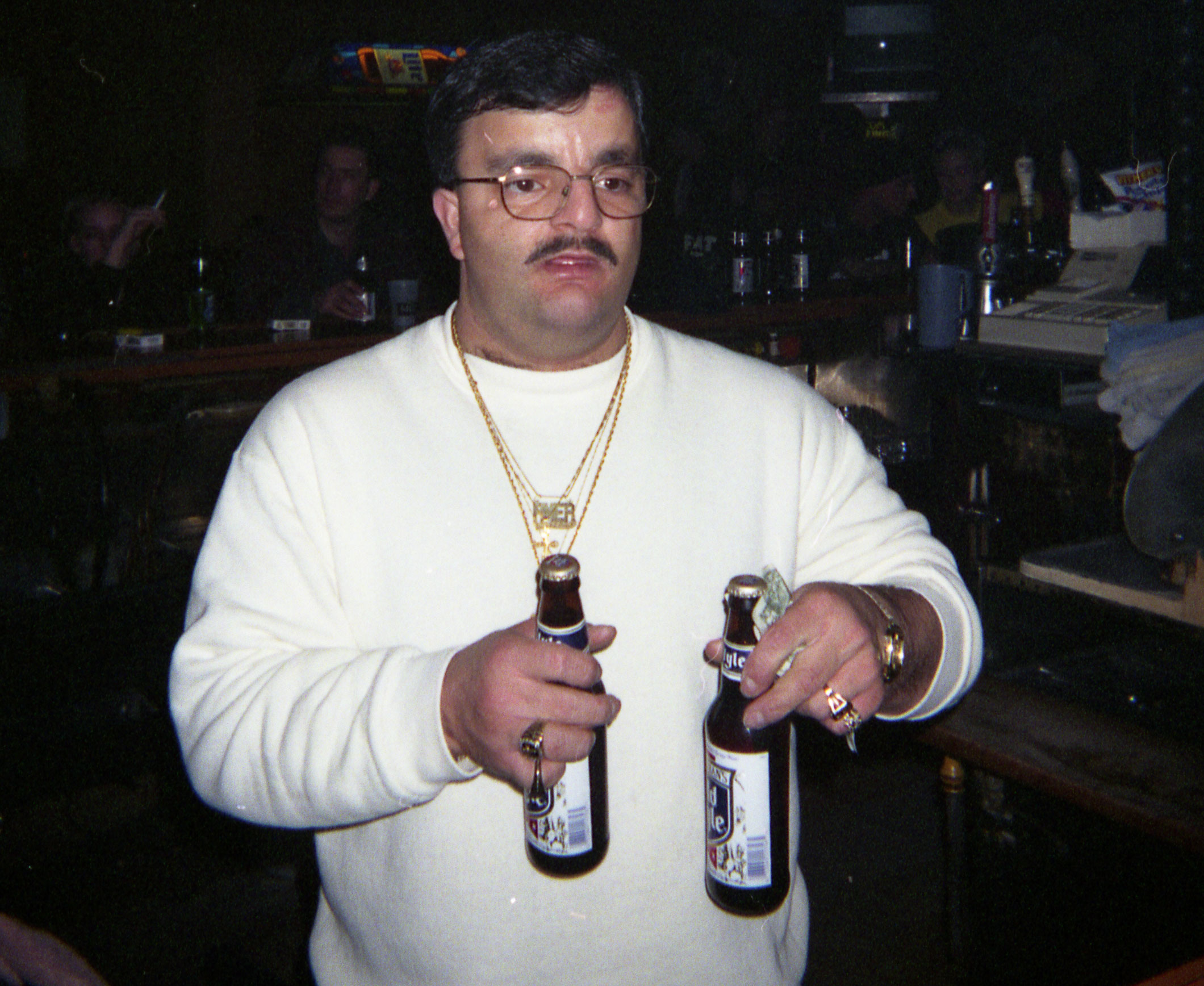

Hammer worked at the Fireside as a bartender, though his bartending skills were questionable.

Hammer worked at the Fireside as a bartender, though his bartending skills were questionable.

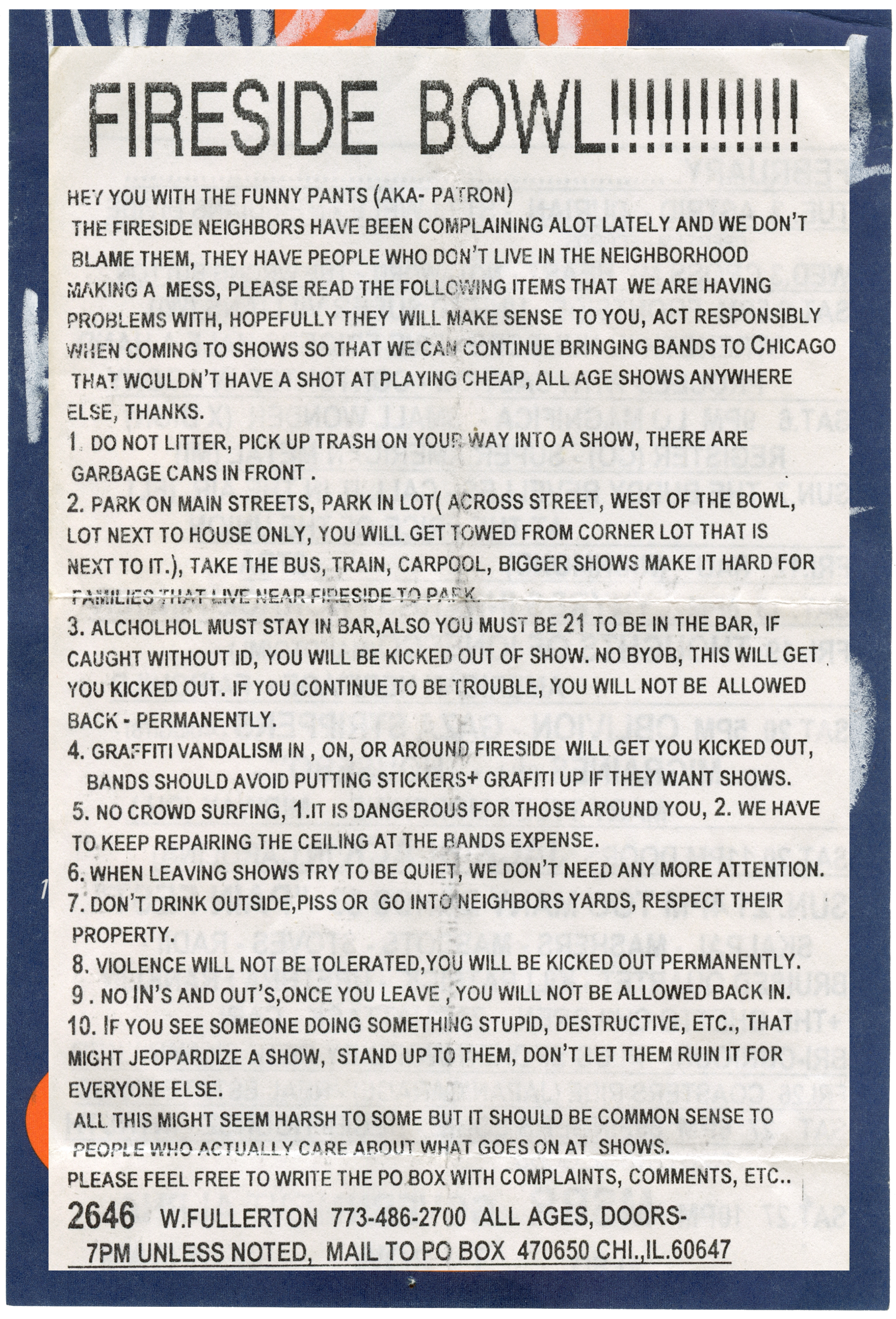

The venue was selling out shows — and often going way over capacity.

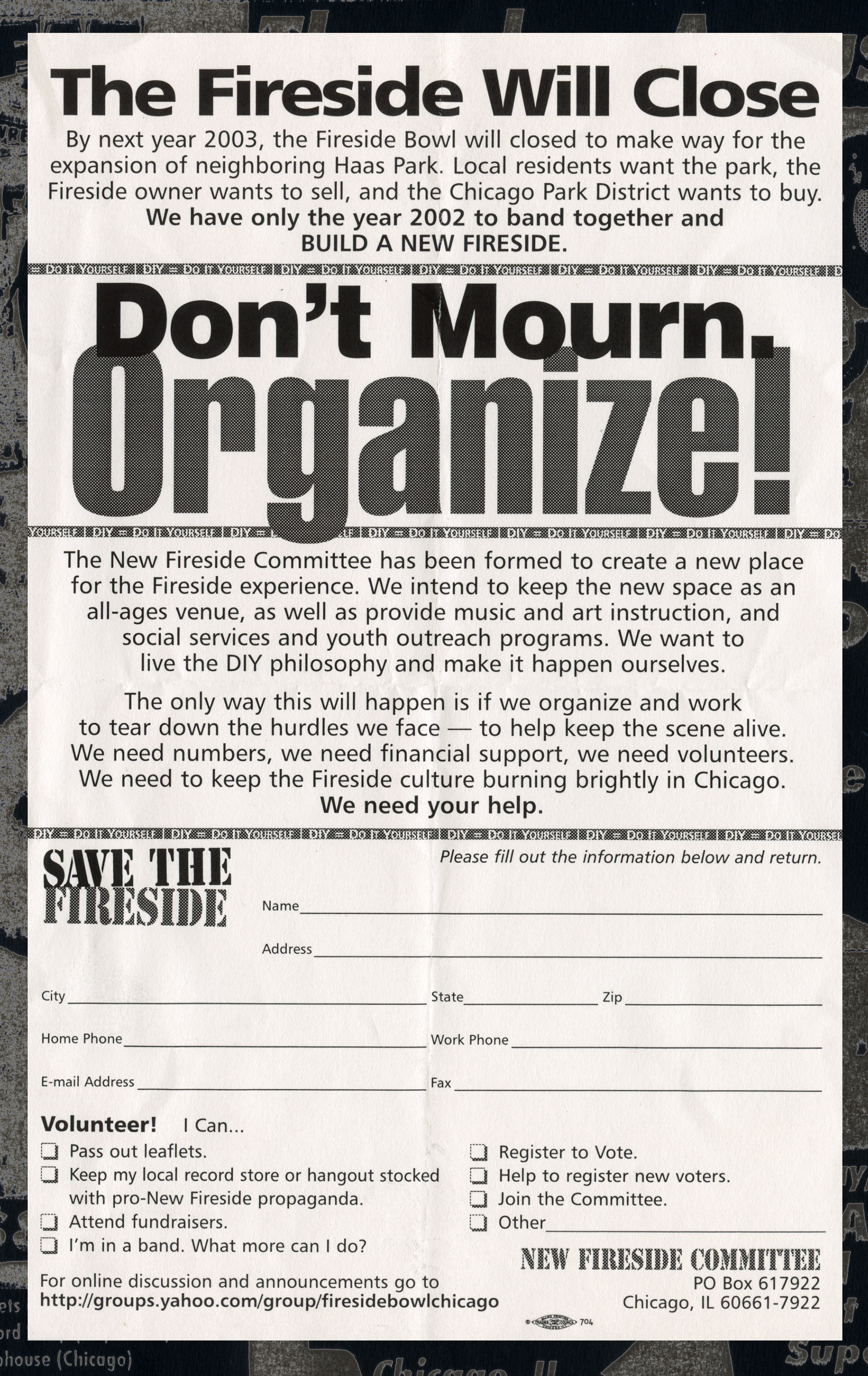

The venue was selling out shows — and often going way over capacity. But the Fireside’s troubles went beyond complaints from neighbors and visits from police. Starting in the early 90s, the city pushed to seize several buildings on the 2600 block of Fullerton Ave., including the Fireside, using eminent domain. The neighborhood was changing. The city wanted to expand Haas Park, located just west of the venue, to create more greenspace.

But the Fireside’s troubles went beyond complaints from neighbors and visits from police. Starting in the early 90s, the city pushed to seize several buildings on the 2600 block of Fullerton Ave., including the Fireside, using eminent domain. The neighborhood was changing. The city wanted to expand Haas Park, located just west of the venue, to create more greenspace.

![‘I eventually moved just down the street [of the Fireside],’ said Fireside regular Rebar A. Rakstad, ‘so there would be times that my roommate would call me and say, 'They're about to go on!' and I would hop on my bike and head over.’](https://cdn.wbez.org/image/142e929da460e4bbfed9317ed2055972)

Boyd, who drives the truck, used to be a Chicago bus driver. “Buses just go straight,” she said, but the garbage truck is different. “We have to do a whole lot of turns and backing up … I still get nervous.”

Boyd, who drives the truck, used to be a Chicago bus driver. “Buses just go straight,” she said, but the garbage truck is different. “We have to do a whole lot of turns and backing up … I still get nervous.”

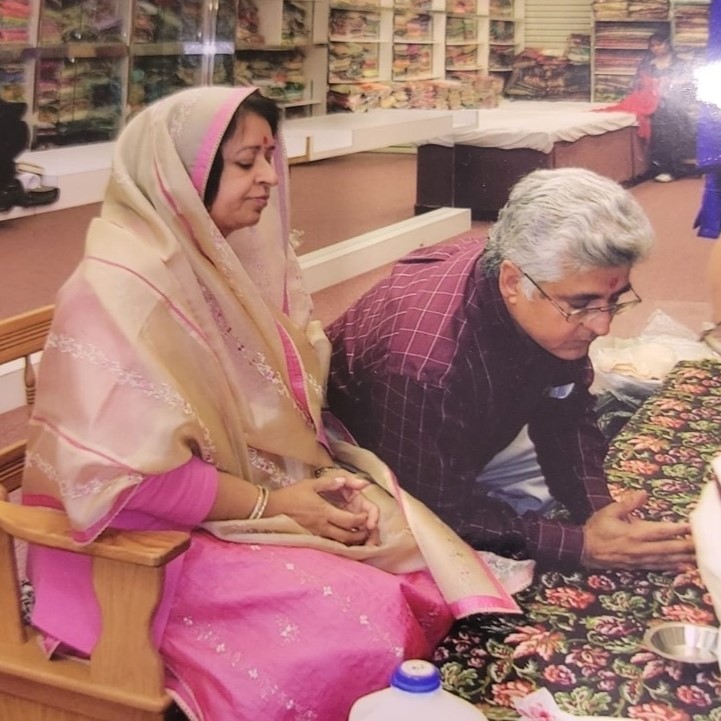

Viral Shah, who helped organize the parade in Naperville, said these are important issues. People want stores to be updated and organized. Potential suburban visitors might think twice before heading out to West Ridge if they know they’ll have a hard time parking or end up with a ticket.

Viral Shah, who helped organize the parade in Naperville, said these are important issues. People want stores to be updated and organized. Potential suburban visitors might think twice before heading out to West Ridge if they know they’ll have a hard time parking or end up with a ticket.

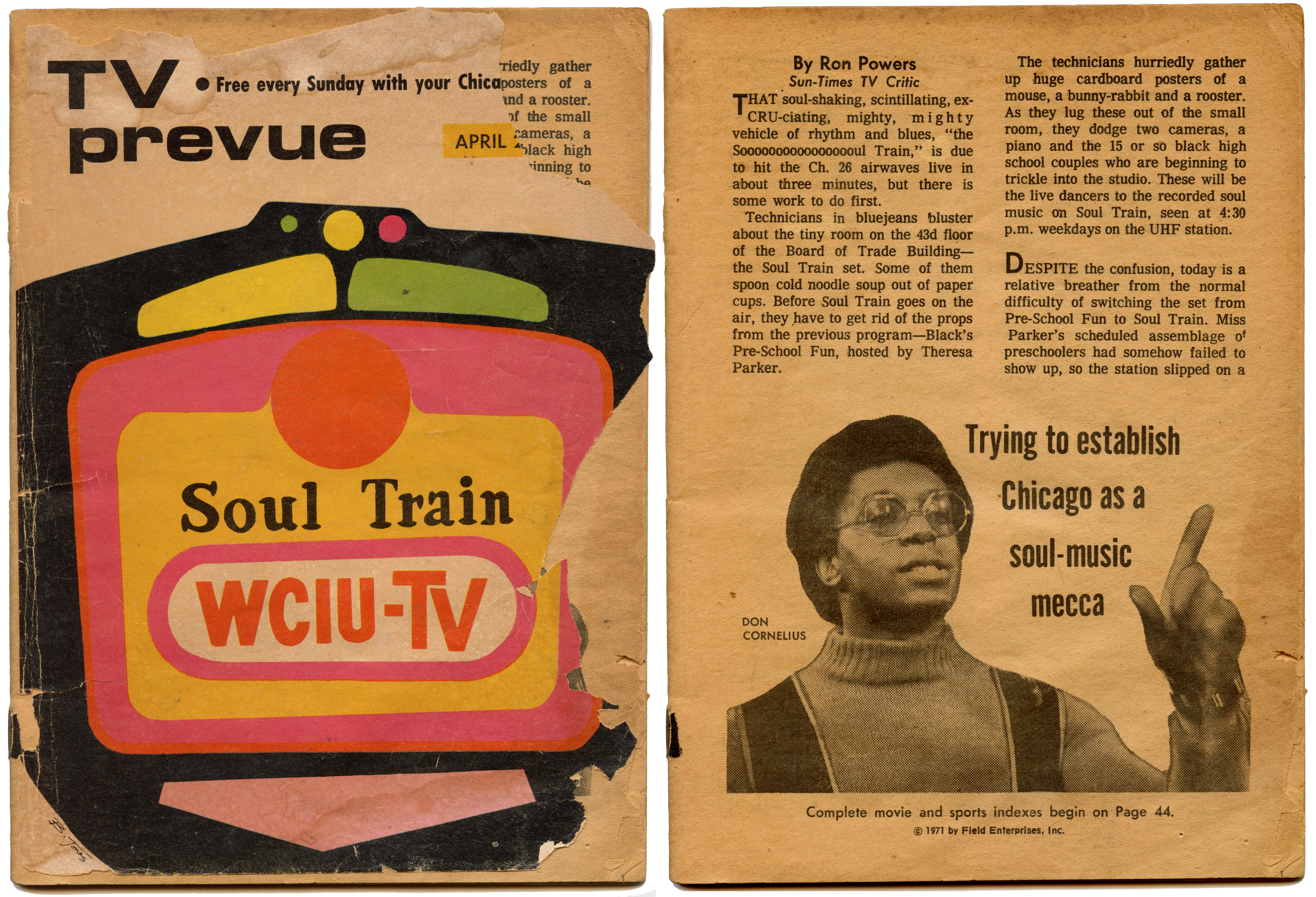

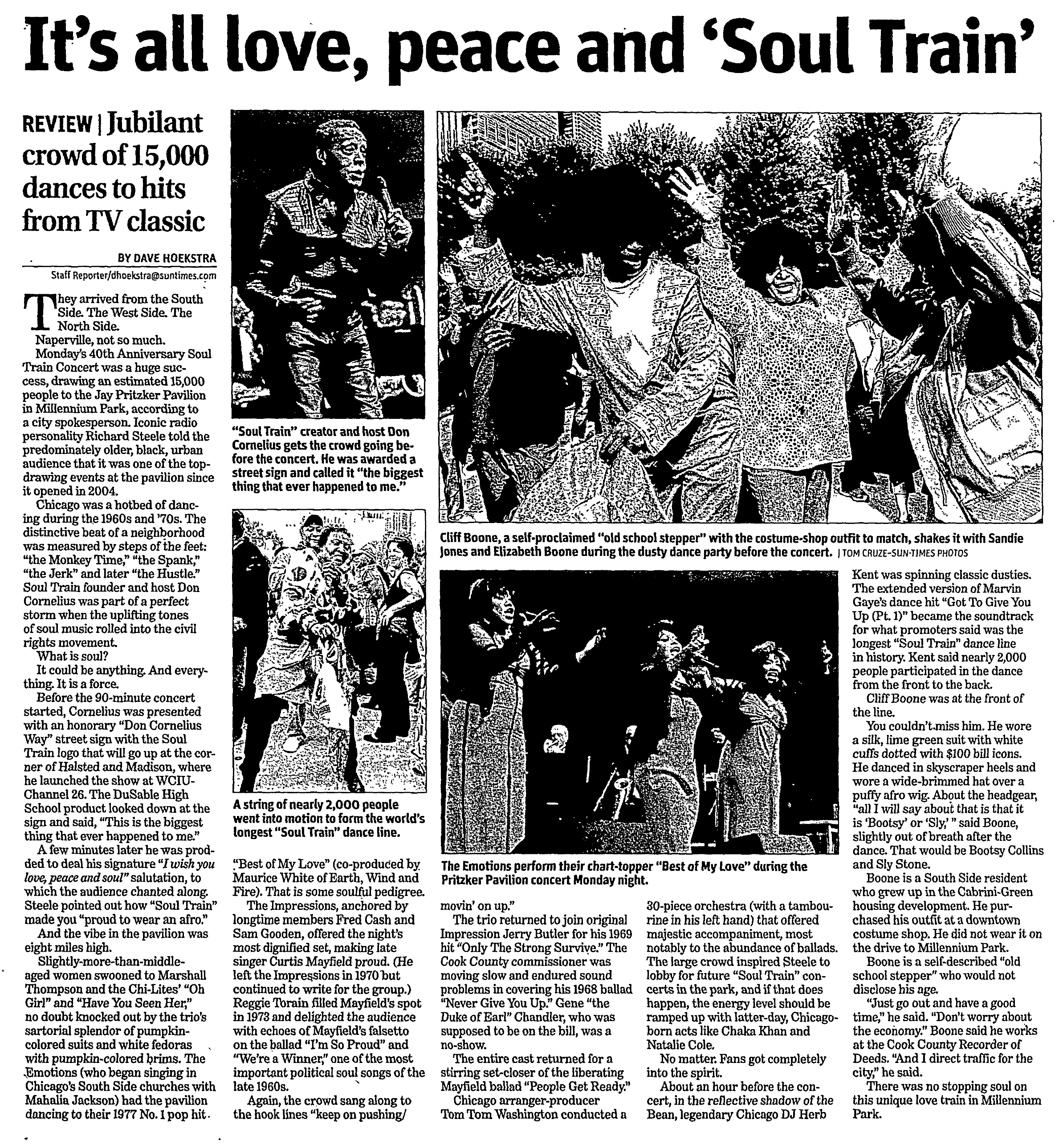

“That was incredible,” said former WBEZ host Richard Steele, a longtime radio personality and friend of Cornelius. “It was the 40th anniversary of the program, but it was also a celebration of Don Cornelius. That had never happened in Chicago, celebrating him even after all of his successes. And this was he was almost in tears, and he was not a guy to really shed tears.”

“That was incredible,” said former WBEZ host Richard Steele, a longtime radio personality and friend of Cornelius. “It was the 40th anniversary of the program, but it was also a celebration of Don Cornelius. That had never happened in Chicago, celebrating him even after all of his successes. And this was he was almost in tears, and he was not a guy to really shed tears.”

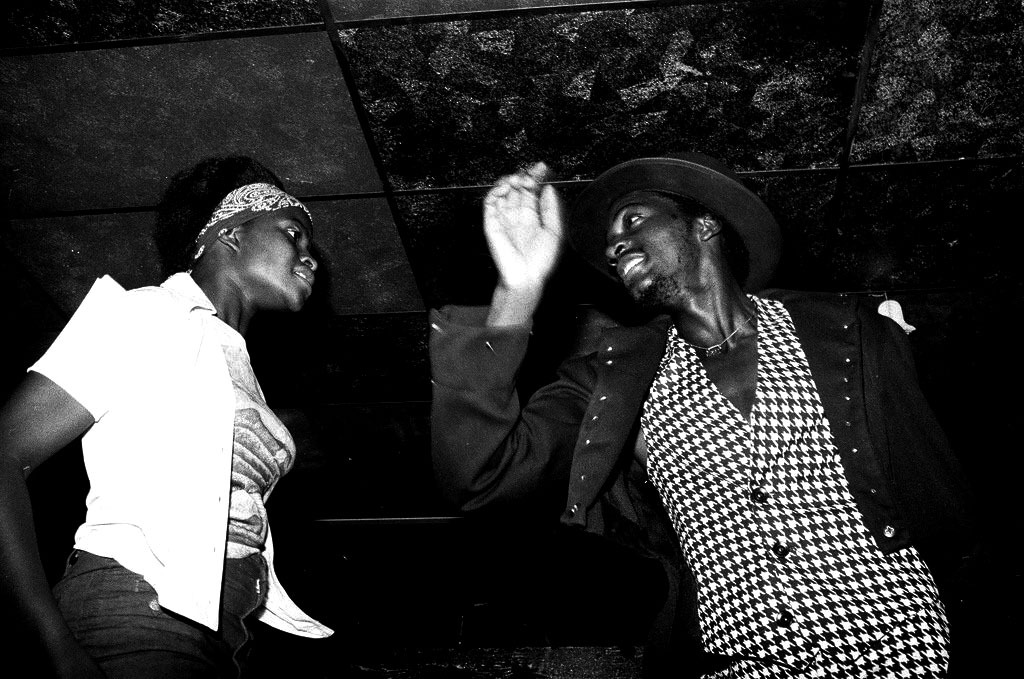

“He was cool,” Steele said. “Don went to DuSable High School. … And if you knew him, you wouldn't say, ‘Oh, this is the erudite television personality.’ No, he's Don from the hood.”

“He was cool,” Steele said. “Don went to DuSable High School. … And if you knew him, you wouldn't say, ‘Oh, this is the erudite television personality.’ No, he's Don from the hood.”

Here in Chicago, Powell says there are new young creatives who are connecting with each other, taking control of their own futures, and creating resources to display Chicago talent to the world.

Here in Chicago, Powell says there are new young creatives who are connecting with each other, taking control of their own futures, and creating resources to display Chicago talent to the world.

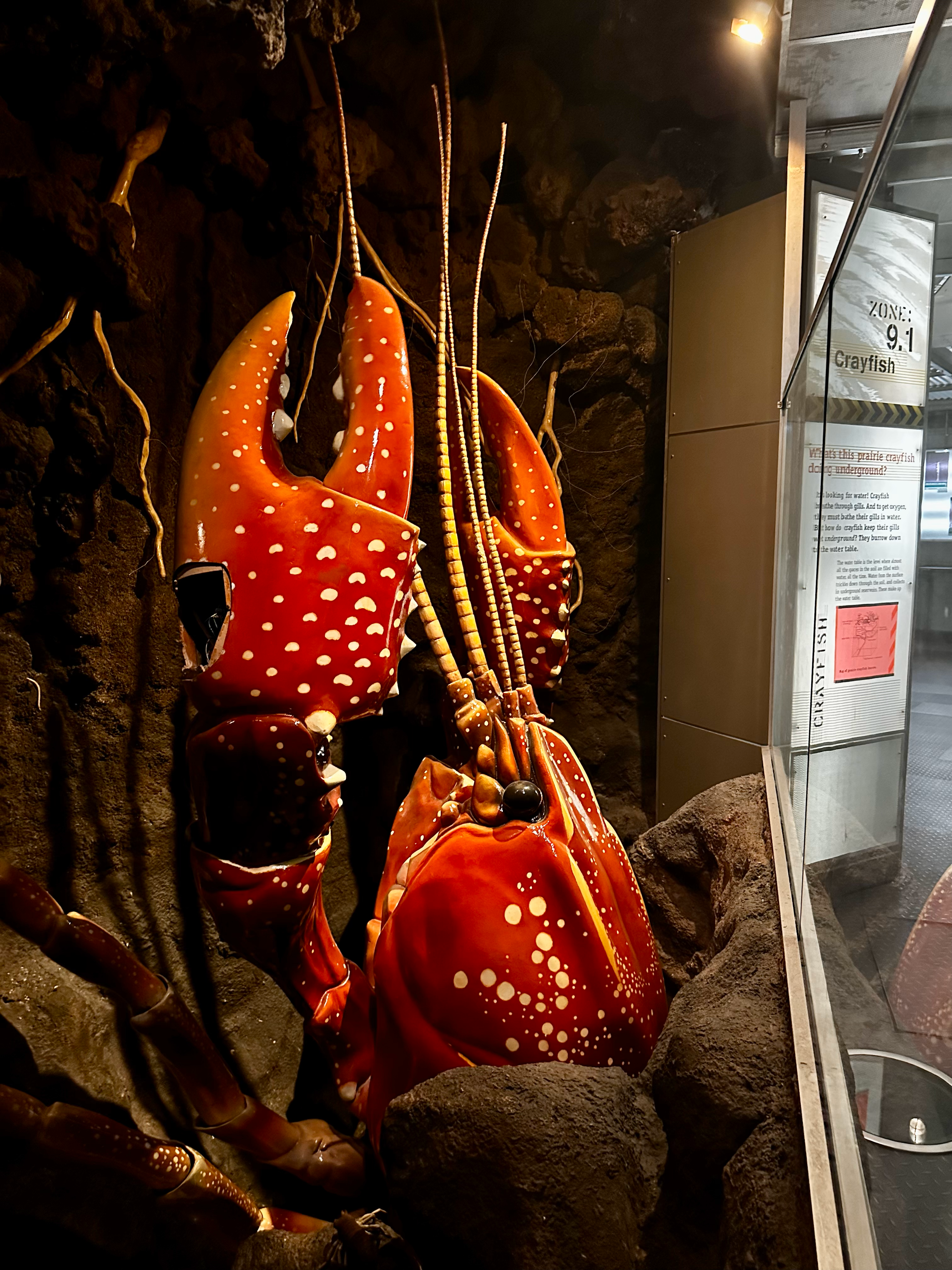

“The red swamp crayfish is a burrowing species,” Keller said. “In some parts of the world, it will weaken levees and lead to levee failure and flooding.”

“The red swamp crayfish is a burrowing species,” Keller said. “In some parts of the world, it will weaken levees and lead to levee failure and flooding.”

For now, his lab currently has about 200 traps in the water, which are emptied out twice a week throughout the summer.

For now, his lab currently has about 200 traps in the water, which are emptied out twice a week throughout the summer.

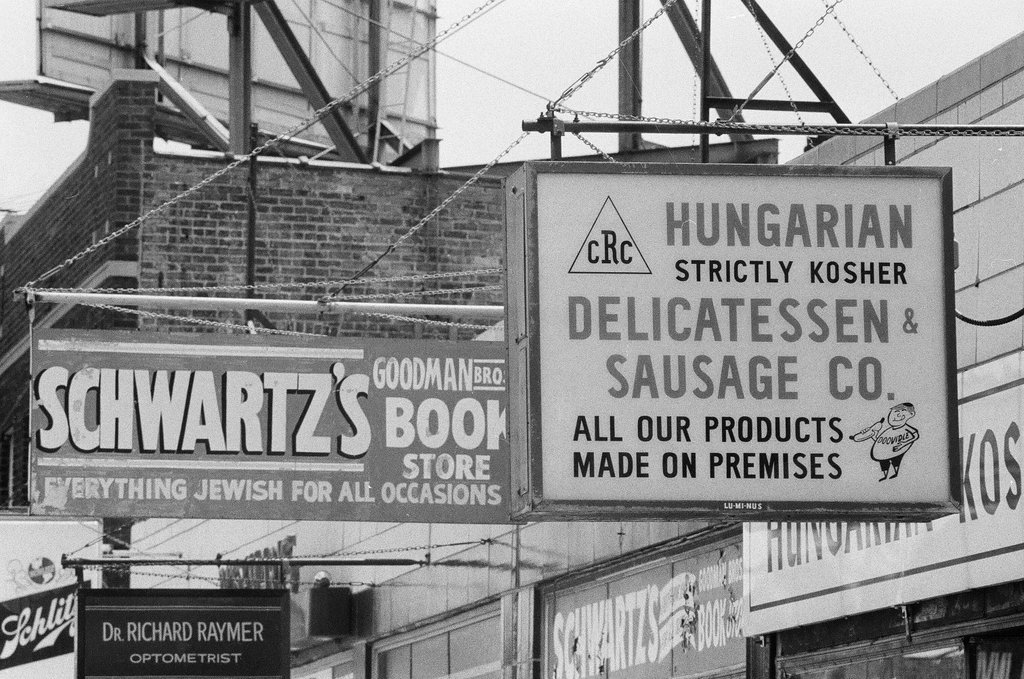

Matanky said that was the general practice in the community for many years. In Orthodox Judaism there is no mixed or family-style seating. Instead, men and women are separated during prayer services. There’s an opaque partition — usually made of fabric or frosted glass — called a mechitza separating the sections.

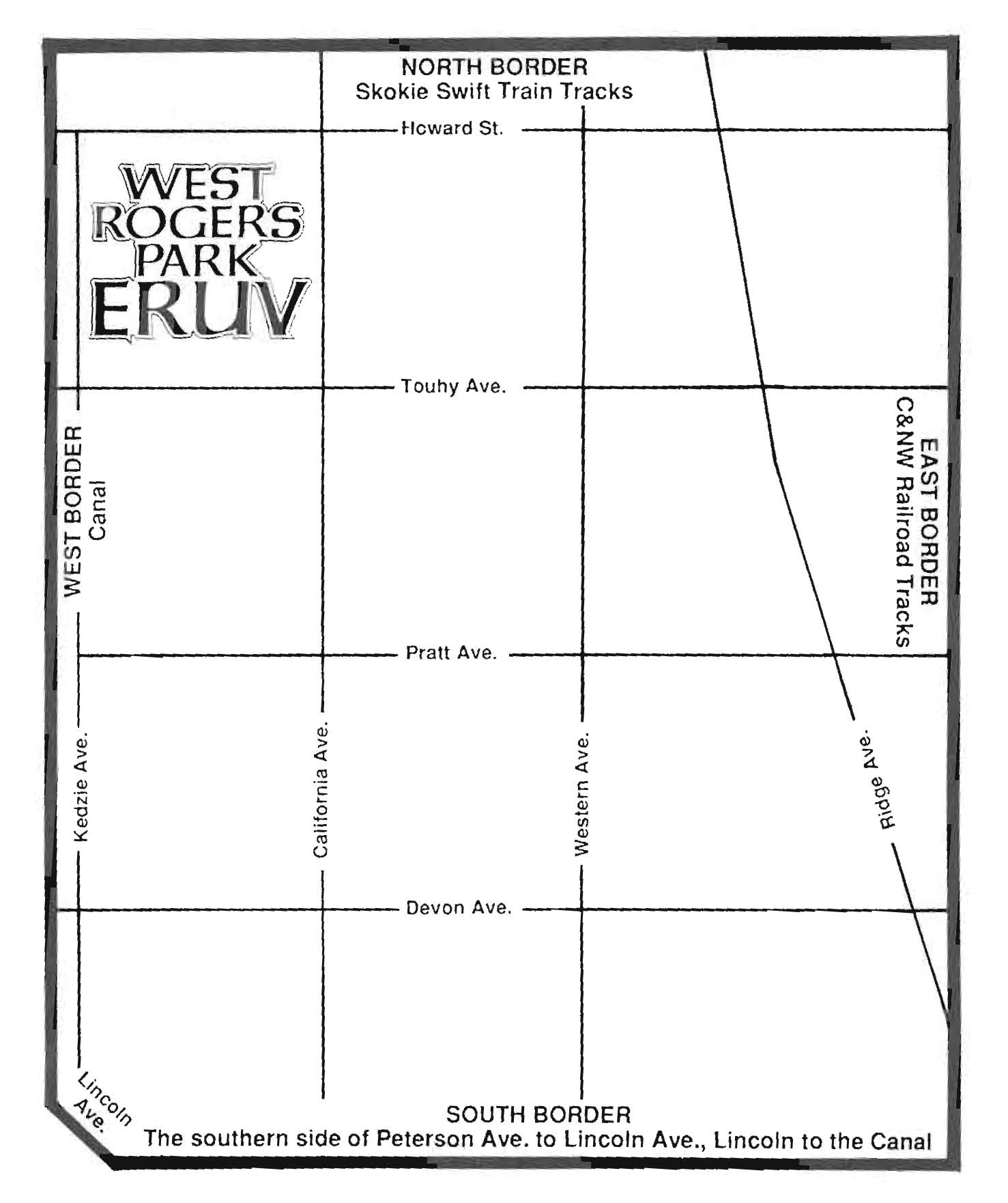

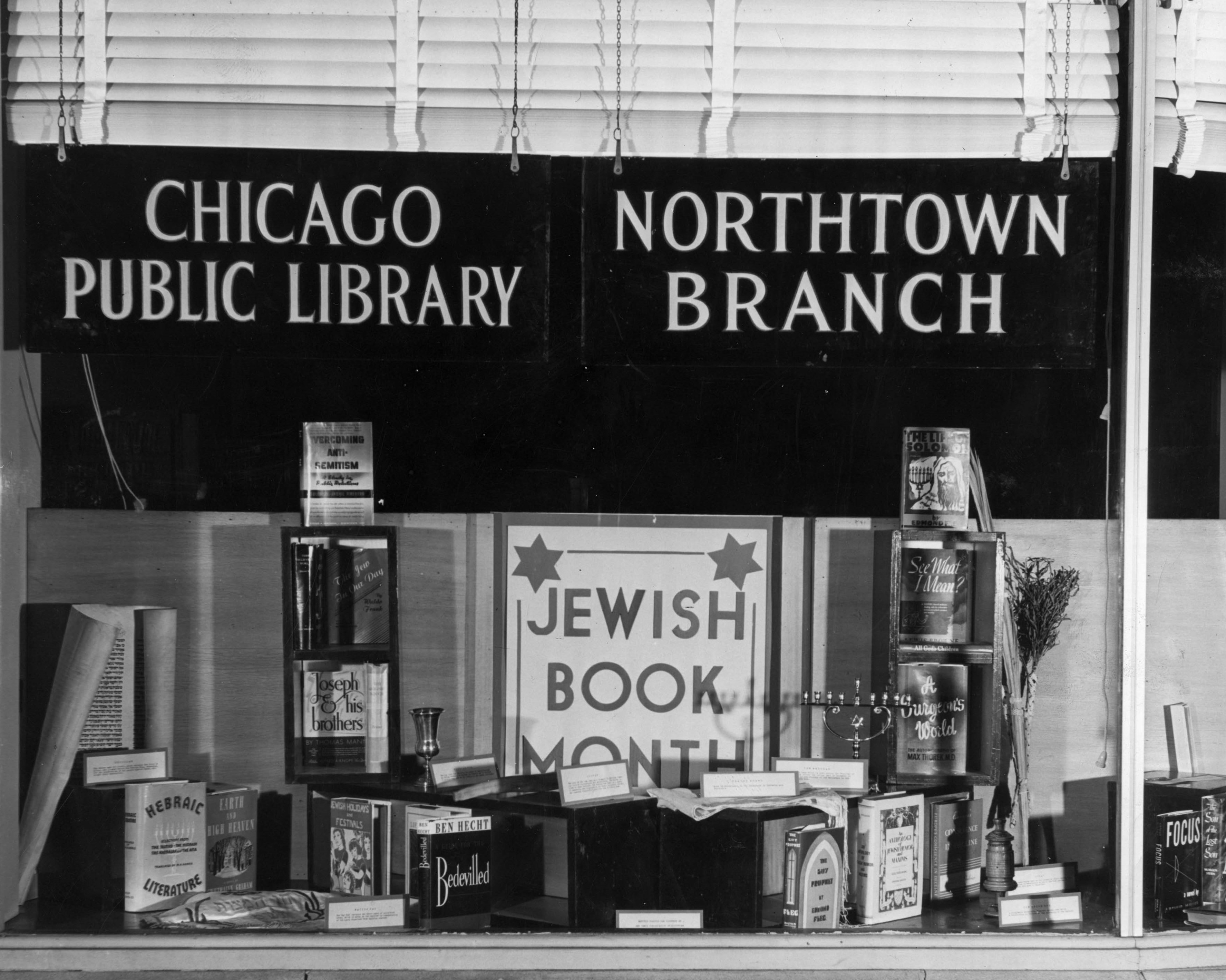

Matanky said that was the general practice in the community for many years. In Orthodox Judaism there is no mixed or family-style seating. Instead, men and women are separated during prayer services. There’s an opaque partition — usually made of fabric or frosted glass — called a mechitza separating the sections. For thousands of years, Rabbis have argued with each other about what exactly “creative” means. It’s boiled down to 39 categories of things you don’t do on Shabbat.

For thousands of years, Rabbis have argued with each other about what exactly “creative” means. It’s boiled down to 39 categories of things you don’t do on Shabbat.

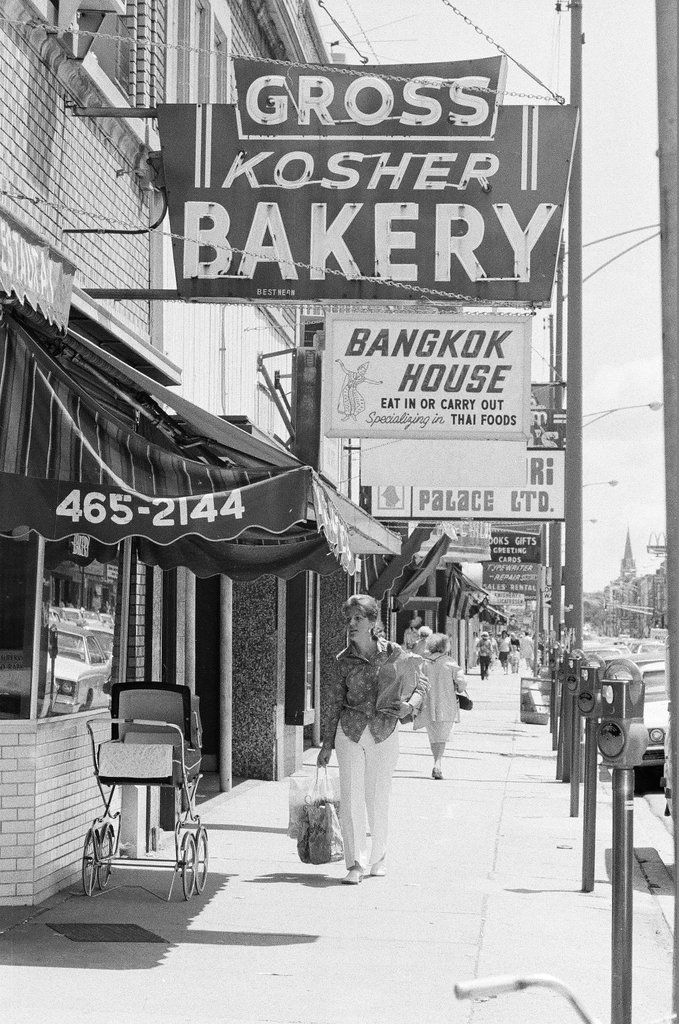

While the Orthodox community has grown significantly in the last couple of decades, this is a very diverse ward.

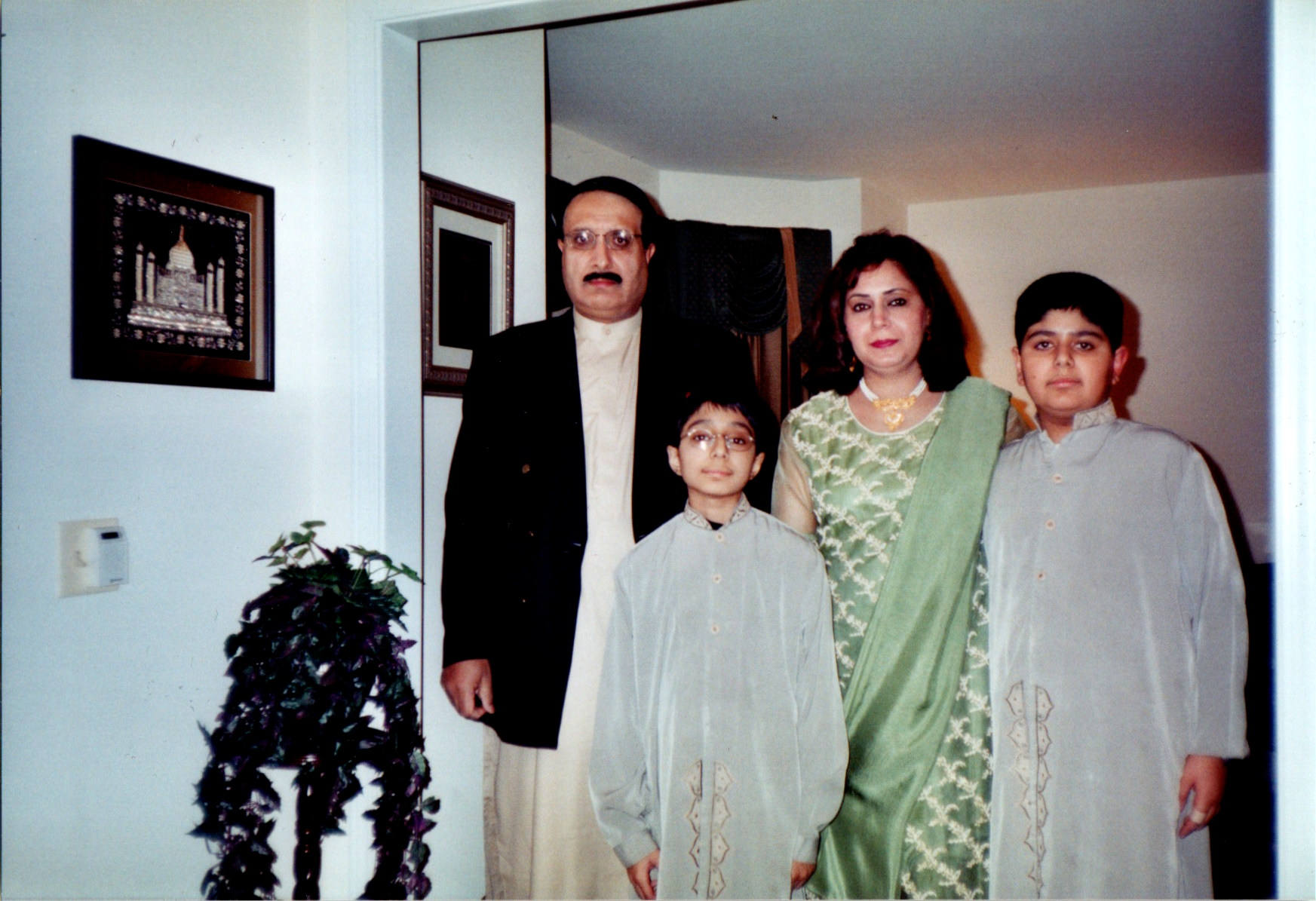

While the Orthodox community has grown significantly in the last couple of decades, this is a very diverse ward. Alice and her family practiced Reform Judaism, which is less strict than Orthodox Judaism about following the traditional rules of the faith. When her parents moved to the West Ridge neighborhood almost 30 years ago, there weren’t many Orthodox families on their block.

Alice and her family practiced Reform Judaism, which is less strict than Orthodox Judaism about following the traditional rules of the faith. When her parents moved to the West Ridge neighborhood almost 30 years ago, there weren’t many Orthodox families on their block.

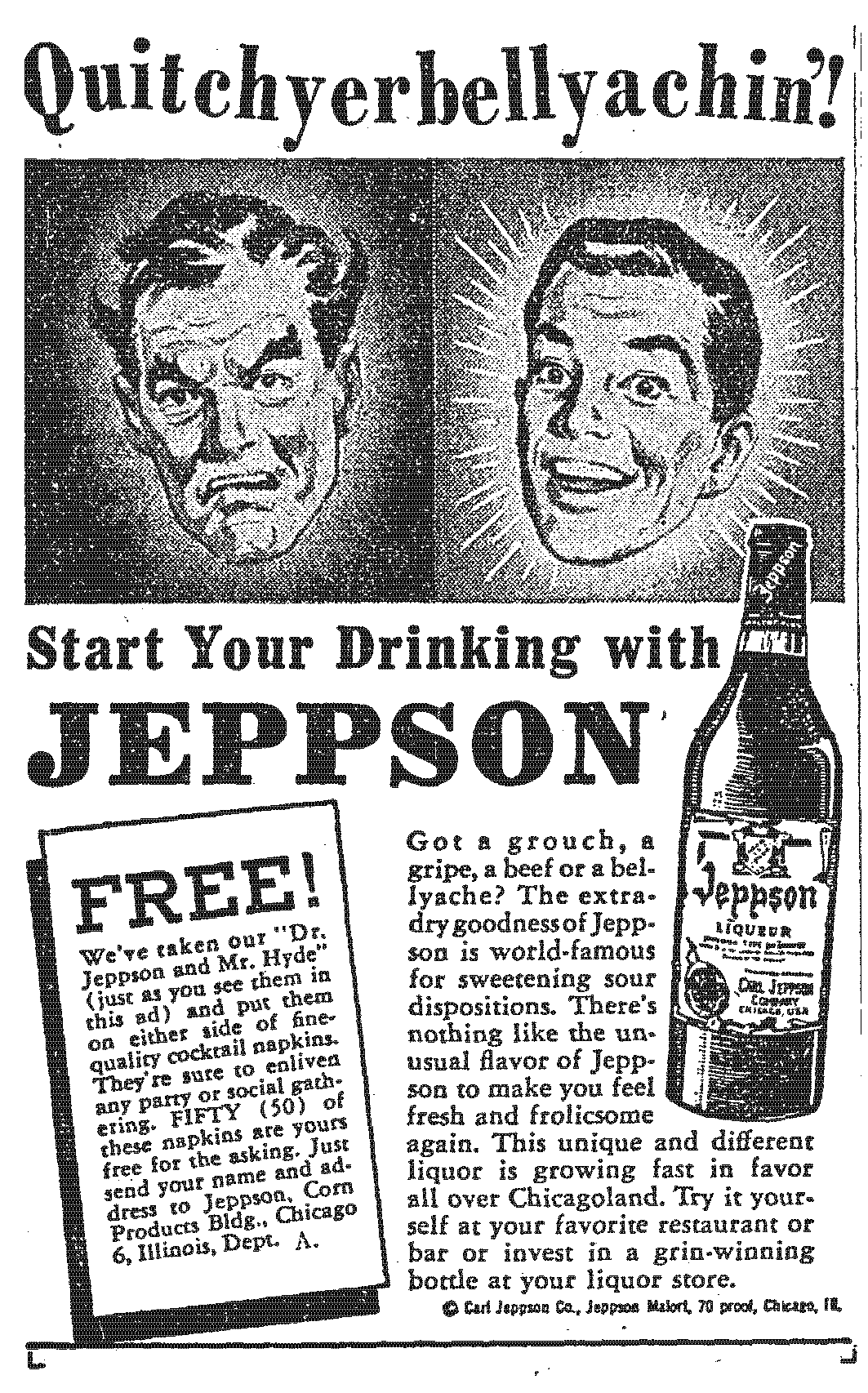

Malört made its debut in Chicago in the 1920s, when Swedish immigrant Carl Jeppson began selling the traditional Swedish-style bitters on the Near North Side. Jeppson skirted Prohibition-era laws by selling his liquor as a tonic to cure stomach worms and parasites. After Prohibition ended, Jeppson sold the recipe, and the first bottles of Malört were produced. In the mid ’40s, the liquor, which is similar to absinthe, was available for purchase in glass bottles with a stem of wormwood inside. Malort developed a steady customer base, but it never really became a popular drink. After all, it wasn’t known to win people over with its flavor.

Malört made its debut in Chicago in the 1920s, when Swedish immigrant Carl Jeppson began selling the traditional Swedish-style bitters on the Near North Side. Jeppson skirted Prohibition-era laws by selling his liquor as a tonic to cure stomach worms and parasites. After Prohibition ended, Jeppson sold the recipe, and the first bottles of Malört were produced. In the mid ’40s, the liquor, which is similar to absinthe, was available for purchase in glass bottles with a stem of wormwood inside. Malort developed a steady customer base, but it never really became a popular drink. After all, it wasn’t known to win people over with its flavor. Soon he started introducing it to his friends at birthday parties and gatherings. He became obsessed with seeing people’s first reactions, which have since become known as “Malört face.” He began hosting Malört-themed trivia nights and comedy shows at local bars.

Soon he started introducing it to his friends at birthday parties and gatherings. He became obsessed with seeing people’s first reactions, which have since become known as “Malört face.” He began hosting Malört-themed trivia nights and comedy shows at local bars.

Today, Mechling heads his own marketing company in Ohio — but the guerilla fandom that he started in the late 2000s carried on after he left.

Today, Mechling heads his own marketing company in Ohio — but the guerilla fandom that he started in the late 2000s carried on after he left.